A homeless guy who set up camp down the road from my place in Mississippi suffered what I suspect was, at least partly, a mosquito-borne psychosis. The consensus among the neighbors was that he had simply lost his mind. But losing your mind is never a simple matter -- a mind has to go someplace to get lost, and if, whenever it gets there, it finds its body tormented by mosquitoes, 24 hours a day, it’s liable to do far crazier things than it might otherwise have done.

I’m talking about a guy standing alone in the woods shouting, “God-damn it! Quit! Quit!” for hours on end, so that a synaptically stable person who lived within earshot came out of his house one morning, heard it and noted: Meltdown. When the person who lived in the house returned from the grocery store several hours later, he observed that the rant was still going on; even later, as he sat on the sofa watching TV, he realized (during the brief lull in the audio), that the voice yet cried in the wilderness; it did so deep into the night.

I wouldn’t disagree that the guy’s behavior was, for lack of a better word, crazy, and there had been plenty of other signs and portents. But one day, when the incessant buzzing of mosquitoes in my ears drove me to my own tiny breaking point, and I began shouting at them, I thought of him and wondered.

Another neighbor had reported hearing endless counting in the vicinity of the homeless guy’s sad little camp, much like chants, going up into the thousands, for hours on end. Was this, I wondered, perhaps a manic enumeration of mosquitoes? Whether the mosquito mania was cause or effect is hard to say, but sitting alone in the woods for days on end, with nothing to do, is one thing, and doing so while being eaten alive by mosquitoes is another.

I never had a chance to confirm my suspicions about the homeless guy’s breaking point – the sheriff’s deputies eventually escorted him off the property. But I'm pretty confident about the role mosquitoes played in pushing him, if not over the edge, at least into a realm that most of us fortunately never go. People tend to want to distance themselves from his sort of behavior, and rightly so. It’s like wanting a screened porch. If you knew about this person, you would feel sorry for him, but you would not likely attempt to intervene. That’s what deputies with Kevlar vests and loudspeakers are for.

The homeless guy spent the entire summer squatting on someone else’s property, without even a tent. It was a long, hot summer, most of it with relatively low mosquito activity, owing to a drought, but it was bookended by the inevitable counterbalance – droves of mosquitoes that were basically looting the world, with nothing to lose. By the end of August they were emerging from high-mortality conditions and no doubt instinctively knew they were headed, in a few short months (a lifetime for a mosquito) into colder weather. Once they got the moisture they needed to reproduce, they began dive-bombing every living thing.

For those of you who do not already know, because you are, what? school children? I should point out that when I refer to “mosquitoes” I’m talking about the females, which are the ones that bite. As a result of what seems a creator’s oversight, the females need more protein than they can generate on their own to develop their eggs, and the only way for them to get it is by stealing it. I suppose you could argue that we steal protein, too, from cows and tofu and so forth, but at least we build things, right? Mosquitoes take and take and appear to give nothing in return, which is another reason to hate them, if we needed one. One wonders: Is their dreadful buzzing and biting really necessary, from a cosmic perspective? Someone (me) innocently emerges from his house, planning only to take out the garbage, and therefore has not bothered to slather on ridiculous amounts of Deep Woods Off; is this really reason for parasitic party time?

I’m into the whole positive and negative forces of the universe thing. I understand that you have to have the good and the bad. God needs Satan, and the feeling is mutual. But sometimes the balance seems to tilt too far in one direction, which appears very much to be the case with mosquitoes. Normally, nature doesn’t like it when any one organism triumphs too well. The natural response is to strike the victor down. Why is that not the case with… vectors?

Seriously, this September. I have never seen the like of mosquitoes in Mississippi. It’s not possible to go outside at my house, which, admittedly, stands near the confluence of two sluggish creeks, without being bitten. If you spray yourself down with bug repellent they go after your eyes and lips and into your ear canals. Forget peeing outside. I love summer, and don’t mind when it’s 100 degrees and 90 percent humidity outside, but at times like this the idea of a frost holds certain attractions. And I say that knowing that “we need a hard freeze to kill the bugs” is total nonsense – it doesn’t work. Even after we get hit by one of those “Arctic clippers” that keep the weather channel people engorged between tornado outbreaks, when the temperature goes down to 14 degrees and everyone’s pipes freeze, two days later it’s 70 degrees and the mosquitoes are back at it. They apparently have places they can go, unlike the homeless guy down the road.

To put this September in context, it was extremely dry in July and August, and after a tropical storm came through and dumped a foot of rain on us, everywhere became an emergency mosquito breeding ground. Wedged between protracted drought and inevitable colder weather, they went on a hedonistic binge, which required blood, and lots of it. Their behavior reminded me of how bad the mosquitoes sometimes get on Horn Island, out in the Gulf, where, when you step ashore with your attractively exposed and remarkably thin skin, word quickly spreads among a population that must otherwise stick its probosci into animals protected by fur, feathers or hides that are used in the manufacture of handbags and cowboy boots. You, in your board shorts, are a mosquito’s dream come true.

At Holly Grove, therefore, retrieving something from the woods behind the garage – a den of unparalleled mosquito fervor – means putting on a rain coat, with a hood, when there isn’t a cloud in the sky, and meanwhile withdrawing your hands into the sleeves, like children do. Even then, you’re liable to get bitten on the nose.

My dog, whose name is Girl, spends her days lying or walking in a cloud of mosquitoes, her coat frightfully adorned with scores of them at any given moment. She is a veritable moveable feast. I’ve tried spraying her with Off, too, because it’s an awful sight to see, this unchecked mosquito-feeding upon your dog, but all that’s accomplished is to make her run from me when she sees me with the can. In order to pet Girl Dog I have to let her into the house, which is not so attractive for her as it normally would be, because I have to wave my hands over her and hurry her along to disperse the hordes of mosquitoes and prevent her from escorting them inside. Even when I’m outside, slathered with Off, and see Girl Dog approaching, I dread her getting near because I know what attends her. Sometimes, in fact, the tiny universe of mosquitoes gets to me before she does. I have, on occasion, when walking to my truck, resorted to running to avoid being repeatedly bitten, and once safely inside, have heard the tiny menacing sound of mosquitoes tapping on the glass. Seriously: There is such a sound. It’s insane, which is why I felt especially sorry for the homeless guy, and also why I decided to do some internet research to find out what it would be like if there were no more mosquitoes in the world, forever and ever amen.

Would that be a bad thing – the disappearance of mosquitoes, which are, you know, one of God’s creations, etc.? I know it would be nice for us, but I also know about what biologists refer to as the “web of life,” and the interconnectivity of species, and how if you remove one thing (even if it is, to us, a bad thing), it can have dangerous consequences for everything else. Like, if you got rid of all the snakes, you’d be overrun with mice and rats and thus, the plague. Every single thing plays a role. But, I wondered, would it be worth sacrificing a few good things, if that’s what it took, to rid the world of mosquitoes? I mean, if something has to go extinct, could it not be them?

You could argue, as some biologists do, that mosquitoes provide food for birds, or whatever, or even that, like viruses, they keep various populations in check, including ours. But if you argued that, who would vote for you? Even biologists who study mosquitoes, who’ve formed their professional identities around them, and make money from studying them, tend to admit that they’re basically a bad thing. These are people who submit tranquilized mice to captive mosquitoes, which then drain the mice of their blood, for science. The mosquitoes, by the way, would do the same to you if you sat out in the woods long enough. They would actually suck you dry.

The best source of information I found online for fantasizing about a world without mosquitoes – anopheles snuff porn, if you will – was an article in the July 2010 issue of Nature magazine titled “A World Without Mosquitoes,” which summarized its findings this way: “Eradicating any organism would have serious consequences for ecosystems — wouldn't it? Not when it comes to mosquitoes, finds Janet Fang.”

Fang. OK. The author.

What Janet Fang found, among other things, was that a scientist at Maryland’s Walter Reed Army Institute of Research actually raises mosquitoes, feeding the larvae ground-up fish food and offering “gravid females” blood to suck from the bellies of unconscious mice — they drain 24 of the rodents a month, and who (the scientist) has been studying mosquitoes for 20 years, yet “would rather they were wiped off the Earth.” The last part serves as a reminder that the scientist is, in the end, comprised of flesh and blood. One wonders if she’s ever tempted to open the door to her mosquito chamber and bomb it with Raid.

The scientist’s sentiment, Fang writes, “is widely shared,” if for no other reason than that malaria, which is borne by mosquitoes, infects some 247 million people worldwide each year, and kills nearly one million. Mosquitoes also spread yellow fever, dengue fever, Japanese encephalitis, Rift Valley fever, something with the catchy name of Chikungunya virus, and West Nile virus. Plus, in the Arctic, mosquitoes form swarms thick enough to asphyxiate caribou.

If, by magic, the world’s 3,500 species of mosquitoes (only “a couple of hundred” of which bite or otherwise bother humans) disappeared, the drawbacks would be largely acceptable, according to the article. Sure, some insects, birds and fish would lose a food source, and some plants would not get pollinated, but the consensus seems to be: So, what?

As the Nature article notes, “in many cases, scientists acknowledge that the ecological scar left by a missing mosquito would heal quickly as the niche was filled by other organisms. Life would continue as before — or even better.” I should point out that there’s a hidden message in that statement, which is that if mosquitoes disappeared, something else would start biting us just as bad. Insect ecologist Steven Juliano, of Illinois State University, in Normal, told Fang that when it comes to the major disease vectors, it’s difficult to see what the downside would be to the removal of mosquitoes, other than what he characterized as “collateral damage.”

“Collateral damage” is a freighted term, if ever there was one, and no doubt some scientists would disagree with the Normal guy’s assessment. A world that is safer for humans is not necessarily a stronger world, after all. But for most of us the disappearance of every last mosquito on Earth would, not surprisingly, be viewed as pretty good news.

The article also quotes a North Carolina entomologist who observed that without mosquitoes the number of migratory birds which nest in the tundras of the far North could be cut in half, due to the loss of a primary food source. The article does offer a disclaimer that some scientists believe the seasonal abundance of mosquitoes in the tundra – and thus, their importance as a food source for wildlife -- may be overestimated, for the simple reason that they’re so annoyingly attracted to us. Sometimes it’s hard to see the forest for the mosquitoes, in other words.

Among the potential ramifications of a theoretical worldwide mosquito eradication, perhaps the most interesting involves those caribou herds, which are thought to select their migratory paths facing into the wind for the purpose of escaping mosquito swarms. As the article notes, “A small change in path can have major consequences in an Arctic valley through which thousands of caribou migrate, trampling the ground, eating lichens, transporting nutrients, feeding wolves, and generally altering the ecology. Taken all together, then, mosquitoes would be missed in the Arctic — but is the same true elsewhere?”

Well, yes, in fact. Some species of fish would likely go extinct without mosquitoes, according to the article, including the appropriately named mosquito fish (Gambusia affinis), which would cause a ripple effect throughout the food chain. Many species of birds, insects, spiders, salamanders, lizards and frogs would also lose a primary food source. This would happen, basically, all over the world. Mosquitoes breed everywhere there is moisture, with some needing stagnant bodies of water but others requiring only a puddle in a tree stump or an old tire, or even the moisture that condenses on the undersides of leaves. Mosquitoes feed on decaying leaves, organic detritus and microorganisms, and they can do their thing in a very short time, such as during the brief summers of the otherwise frozen North.

One scientist quoted in the article agreed that despite the downsides, other organisms would fill the void if mosquitoes disappeared, and offered the not-entirely-reassuring analogy that, “If you pop one rivet out of an airplane's wing, it’s unlikely that the plane will cease to fly.” Still, some of the downsides would be impossible to predict. As a New Jersey scientist pointed out, people would also love to get rid of biting midges commonly called no-see-ums, but if that happened, tropical crops of cacao would no longer get pollinated, which, perhaps more alarmingly than the specter of a planet losing one of its wing-rivets, “would result in a world without chocolate.”

Obviously, the ramifications of planet-wide mosquitocide are debatable. As Fang notes, mosquitoes provide an ideal route for the spread of pathogenic microbes, yet those, too, are crucial to that pesky web of life. In the end, the ecological effect of eliminating harmful mosquitoes would be: More people. “Many lives would be saved; many more would no longer be sapped by disease,” Fang concludes. So: Good for us, and probably bad for the planet.

It’s interesting to think about, but that’s all we’re going to do. Planetary mosquito eradication is not going to happen. Mosquitoes are incomparably adaptable, due to their fecundity and short life spans -- that much we know. But it doesn’t stop us from imagining a world from which they are gone, or of trying to eliminate them from areas nearby.

I remember, as a child, the excitement I and my friends felt when we heard the approaching sound of the compressor on “the mosquito man’s truck,” which, on certain summer evenings, filled the city’s neighborhoods with a thick, white cloud of pungent insecticide. The sound of the mosquito man’s truck was more thrilling even than the tunes emitted by the ice cream truck when it made its presence known a block away. We enjoying running behind the truck, getting lost in the cloud, to emerge, perhaps, on another street, unsure where we were, our respiratory tracts filled with nervous toxins. No one seemed to care about the health risks back then, our only admonition being that we not get hit by cars as we ran into and out of the cloud.

Eventually, due to studies which showed that whatever insecticide was in that fog was harmful to the environment, the mix was changed and the mosquito man’s truck began emitting a clear, boring mist. We sat on our porches and watched the disappointing specter pass us by. At least there were no mosquitoes.

A friend of mine recently told me that he had a new anti-mosquito misting system installed in the eaves of his house, which periodically releases a non-toxic, natural mosquito repellant, which works very well, though only if you’re on the porch or nearby. Chemical insect repellent is likewise only moderately effective, and feels pretty gross. And scientists tell us that bug zappers – those black-light contraptions that people install by their patios, are not only ineffective at controlling mosquitoes but may kill far more beneficial insects, including some that feed on mosquitoes and their larvae. Not that people with bug zappers care. In the endless conflict between us and them, it is enough, apparently, to hear that zap and imagine that there’s one less tiny, insistent, buzzing menace in the crazy, mixed-up world.

Photo originally published in National Geographic.

Tuesday, September 20, 2011

Sunday, September 18, 2011

Author photos

There are two tasks that most writers detest: Pitching story ideas to publishers, and having their author photos made. The former will always be with us; the latter is something that rears its head periodically, dragging with it the weight of years that have somehow failed to steel the author's invariably sensitive ego, which is now charged with publicly personifying both itself and its creation, the book, for skeptical shoppers and for posterity. Vanity, is what it is. Although, I must say, this elderly gent doesn't seem to mind it one bit, and he pulls it off pretty well.

Who shall I be? The pensive author, perusing a book (inevitably, his own), sitting at a desk, refillable ink pen in hand, musing at a computer monitor or, in olden days, a typewriter? Chin resting on the palm of his hand in a paneled study? Glance around the room, surely there’s a pipe in there somewhere. But wait, this guy's actually using one for a prop, still.

Also, those look suspiciously not like books on the shelf behind him, which makes you wonder what he's staring at.

It's possible to pull off the reflective author with pipe thing, of course. This guy did it pretty well -- in fact he's probably got 10 author photos where he's holding the stereotypical prop. It appears to have been a kind of branding, but considering that he's the greatest writer in American history, to date, I guess we should give him a pass.

Then there's the glossy head-shot, with all it evokes about success, but not to the point of implying inaccessibility. Everyone is attracted to good-looking people, right? So long as they don't appear to be overly aware of their good looks. This one works, I think, though it may simply be because she's so pretty.There’s the happy author, the offbeat author, the serious author, the author "in the field," the author posing with his dog, each with their own special lighting, backdrops and facial expressions. And what to wear? You dress like a writer, which is to say, your clothes say very little.

But I keep coming back to... the hand, used as a prop, literally. Lots and lots of those.

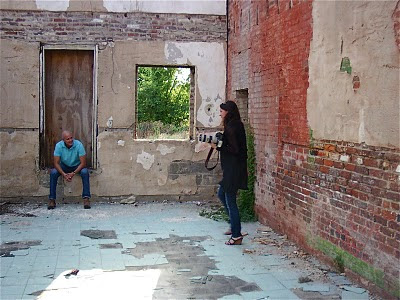

The updating of the author photo is now upon me and the co-author of my next book, Michael Rejebian, and though the photographer we used had an original take, and chose a suitably decadent venue – an abandoned building in the ruined Farish Street neighborhood of Jackson, Miss., she could not quite overcome my distaste for posing for author photos, and it shows.

In most of my author photos I am borderline morose. This one is actually my slightly happy pose. Also, I’m staring away from the camera, as if to say… what? That I don’t know my picture is being taken?

For my first author photo I used a picture taken by my friend Nancy Goldman on the occasion of my 40th birthday trip to Italy. It was a truly candid shot, taken by someone I liked, at a happy time. That’s why it worked so well, right up to the point that at a signing for my book Mississippi in Africa, in 2003, someone asked, in passing, “When was this picture of you taken?” The only possible subtext of the question was that it did not appear to have been taken yesterday. I had to face the fact that as much as I liked to think so, I no longer looked precisely as I had looked just eight years before. I didn’t even know, until the question was asked, that it had been that long.

This is how you get those occasional obituaries in the newspaper where someone who died at age 92 looks, in the photo, as if he wasn’t a day past 40. He just didn't like most of the pictures taken during the last 52 years of his life.

Thus chastened, I arranged to reshoot the Mississippi in Africa author photo for the first paperback edition, using something more “up-to-date.” James Patterson, a very skilled photographer in Jackson, took a series of photos that he and his then-assistant pronounced really wonderful, but in which, I couldn’t help but observe, I looked considerably older than the 27-year-old I still saw myself as.

Next up, the author photo for my book Sultana, taken by a photog friend in New York City, Everett McCourt. It's artistic and striking, but I look a bit ill. Also, I appear to be as grave as a monk -- actually an appropriate look, I suppose, for the author of a book in which thousands of people die, but still.

For the upcoming book, We're With Nobody, I needed to look the opposite of morose, because the book is both serious and funny – quirky, even. But in this effort I was thwarted by the photo-shoot dynamic, in which I appear to be very studiously considering what I look like, to the detriment of how I look.

So I went back to James, who had taken a series of photos at my house for a magazine article, and offered to let me use any of them for my author photo, gratis. For the purposes of the upcoming book, I’d have actually rather gone with something less mainstream, such as the next one you see, below. But at a certain point trying to look “different” speaks to a familiar paradigm – look how little I seem to care about the paradigm of author publicity photos, even as I artificially showcase my face for an author publicity photo. Also, I think this photo is about eight years old now, too. And one of my eyes is open a little wider than the other.

It could be worse, I guess. You could always come off looking strange, like these people who turned up during a Google search of "author photos:"

Or just, not someone whose book you'd want to read.

But there's always the possibility that you'll look cool, middle aged and appropriate to the subject matter, such as my friend Sebastian, who's got a lot to work with.

In the end, I’m thinking of going with this one, taken by James, but I go back and forth. I'm still not looking at the camera, but at least I'm not morose, or weird, and I'm not propping my head up with my hand. Plus, 10 years from now, it’ll look young to me.

Like I said, it's all about purposeful vanity. I've posted a note about the process of selecting a photo of myself, as if you should care, and used it as an excuse to highlight various photos of myself, in none of which does my bald spot show. That is one more reason why this is such a distasteful task. I need you to like my photo.

This is Michael, by the way, having his author photo shot by Christina Cannon:

All of us, when we see ourselves in a photo with a group of people, our eyes invariably land on our own image first. We care how the world sees us, and I can assure you that it's even worse when you need to personify a product that you very much want the world to buy.

Who shall I be? The pensive author, perusing a book (inevitably, his own), sitting at a desk, refillable ink pen in hand, musing at a computer monitor or, in olden days, a typewriter? Chin resting on the palm of his hand in a paneled study? Glance around the room, surely there’s a pipe in there somewhere. But wait, this guy's actually using one for a prop, still.

Also, those look suspiciously not like books on the shelf behind him, which makes you wonder what he's staring at.

It's possible to pull off the reflective author with pipe thing, of course. This guy did it pretty well -- in fact he's probably got 10 author photos where he's holding the stereotypical prop. It appears to have been a kind of branding, but considering that he's the greatest writer in American history, to date, I guess we should give him a pass.

Then there's the glossy head-shot, with all it evokes about success, but not to the point of implying inaccessibility. Everyone is attracted to good-looking people, right? So long as they don't appear to be overly aware of their good looks. This one works, I think, though it may simply be because she's so pretty.There’s the happy author, the offbeat author, the serious author, the author "in the field," the author posing with his dog, each with their own special lighting, backdrops and facial expressions. And what to wear? You dress like a writer, which is to say, your clothes say very little.

But I keep coming back to... the hand, used as a prop, literally. Lots and lots of those.

The updating of the author photo is now upon me and the co-author of my next book, Michael Rejebian, and though the photographer we used had an original take, and chose a suitably decadent venue – an abandoned building in the ruined Farish Street neighborhood of Jackson, Miss., she could not quite overcome my distaste for posing for author photos, and it shows.

In most of my author photos I am borderline morose. This one is actually my slightly happy pose. Also, I’m staring away from the camera, as if to say… what? That I don’t know my picture is being taken?

For my first author photo I used a picture taken by my friend Nancy Goldman on the occasion of my 40th birthday trip to Italy. It was a truly candid shot, taken by someone I liked, at a happy time. That’s why it worked so well, right up to the point that at a signing for my book Mississippi in Africa, in 2003, someone asked, in passing, “When was this picture of you taken?” The only possible subtext of the question was that it did not appear to have been taken yesterday. I had to face the fact that as much as I liked to think so, I no longer looked precisely as I had looked just eight years before. I didn’t even know, until the question was asked, that it had been that long.

This is how you get those occasional obituaries in the newspaper where someone who died at age 92 looks, in the photo, as if he wasn’t a day past 40. He just didn't like most of the pictures taken during the last 52 years of his life.

Thus chastened, I arranged to reshoot the Mississippi in Africa author photo for the first paperback edition, using something more “up-to-date.” James Patterson, a very skilled photographer in Jackson, took a series of photos that he and his then-assistant pronounced really wonderful, but in which, I couldn’t help but observe, I looked considerably older than the 27-year-old I still saw myself as.

Next up, the author photo for my book Sultana, taken by a photog friend in New York City, Everett McCourt. It's artistic and striking, but I look a bit ill. Also, I appear to be as grave as a monk -- actually an appropriate look, I suppose, for the author of a book in which thousands of people die, but still.

For the upcoming book, We're With Nobody, I needed to look the opposite of morose, because the book is both serious and funny – quirky, even. But in this effort I was thwarted by the photo-shoot dynamic, in which I appear to be very studiously considering what I look like, to the detriment of how I look.

So I went back to James, who had taken a series of photos at my house for a magazine article, and offered to let me use any of them for my author photo, gratis. For the purposes of the upcoming book, I’d have actually rather gone with something less mainstream, such as the next one you see, below. But at a certain point trying to look “different” speaks to a familiar paradigm – look how little I seem to care about the paradigm of author publicity photos, even as I artificially showcase my face for an author publicity photo. Also, I think this photo is about eight years old now, too. And one of my eyes is open a little wider than the other.

It could be worse, I guess. You could always come off looking strange, like these people who turned up during a Google search of "author photos:"

Or just, not someone whose book you'd want to read.

But there's always the possibility that you'll look cool, middle aged and appropriate to the subject matter, such as my friend Sebastian, who's got a lot to work with.

In the end, I’m thinking of going with this one, taken by James, but I go back and forth. I'm still not looking at the camera, but at least I'm not morose, or weird, and I'm not propping my head up with my hand. Plus, 10 years from now, it’ll look young to me.

Like I said, it's all about purposeful vanity. I've posted a note about the process of selecting a photo of myself, as if you should care, and used it as an excuse to highlight various photos of myself, in none of which does my bald spot show. That is one more reason why this is such a distasteful task. I need you to like my photo.

This is Michael, by the way, having his author photo shot by Christina Cannon:

All of us, when we see ourselves in a photo with a group of people, our eyes invariably land on our own image first. We care how the world sees us, and I can assure you that it's even worse when you need to personify a product that you very much want the world to buy.

Writing, and the Like

As some of you know, my next book, co-authored with Michael Rejebian, is about doing opposition political research across the U.S., and will be published by HarperCollins in January.

As part of the publicity effort for the book, our publicist has given us a homework assignment: To expand the reader base of my existing online sites, as well as to create a new website and Facebook page for Michael and me that's specifically about the new book, to generate buzz.

If you're like me, you may be a bit resistant to promotional use of Facebook, and if that's the case, feel free to disregard the notification you may receive asking you to "like" the "Alan Huffman Like" page (for lack of a better term to differentiate it from my personal Facebook page, which is also, logically but a bit confusingly, called "Alan Huffman"). The "like" page is where I post links to www.alanhuffman.blogspot.com, as well as updates about other articles and books I've published, author signings, related news stories, etc.

If, on the other hand, you do want to know what's going on with the new book and with my other publications, liking the Facebook page will keep you up-to-date and will meanwhile help us get the word out -- something that's pretty vital now.

Here's the link to the Alan Huffman "like" page (unfortunately, you'll have to copy and paste -- blogspot doesn't automatically convert the url to a hyperlink):

http://www.facebook.com/pages/Alan-Huffman/67586220217?sid=5134bfb0b56">

You can also link to the blogspot and Facebook updates pages from my website, www.alanhuffman.com. The blogspot page gives you the option to be a follower, if you'd prefer that route over Facebook. When the new book website and Facebook page go up, I'll post the links.

As part of the publicity effort for the book, our publicist has given us a homework assignment: To expand the reader base of my existing online sites, as well as to create a new website and Facebook page for Michael and me that's specifically about the new book, to generate buzz.

If you're like me, you may be a bit resistant to promotional use of Facebook, and if that's the case, feel free to disregard the notification you may receive asking you to "like" the "Alan Huffman Like" page (for lack of a better term to differentiate it from my personal Facebook page, which is also, logically but a bit confusingly, called "Alan Huffman"). The "like" page is where I post links to www.alanhuffman.blogspot.com, as well as updates about other articles and books I've published, author signings, related news stories, etc.

If, on the other hand, you do want to know what's going on with the new book and with my other publications, liking the Facebook page will keep you up-to-date and will meanwhile help us get the word out -- something that's pretty vital now.

Here's the link to the Alan Huffman "like" page (unfortunately, you'll have to copy and paste -- blogspot doesn't automatically convert the url to a hyperlink):

http://www.facebook.com/pages/Alan-Huffman/67586220217?sid=5134bfb0b56">

You can also link to the blogspot and Facebook updates pages from my website, www.alanhuffman.com. The blogspot page gives you the option to be a follower, if you'd prefer that route over Facebook. When the new book website and Facebook page go up, I'll post the links.

Friday, September 16, 2011

Mississippi in Africa update

Kaiser Railey, January 2001

It was a remarkable story that seemed to unravel into thin air. Several versions had been in circulation for generations -- for more than 150 years, in fact. But in each of them the screen went blank just as the plot started getting good.

That's precisely how writers find themselves in the throes of writing a book. Once I heard the story of Mississippi in Africa, I had to know how it ended. How could anyone hear that a group of slaves had emigrated from a Mississippi plantation, decades before the Civil War, to a place in Liberia called Mississippi in Africa, and not want to know what had become of them?

The plot was launched in the 1830s, when an antebellum Mississippi cotton planter and Revolutionary War veteran named Isaac Ross decreed in his will that after his daughter’s death his slaves should be freed and his plantation, called Prospect Hill, should be sold, with the proceeds used to pay the way for the freed slaves to a colony established for the purpose on the coast of West Africa, in what is now the nation of Liberia. A very weird story. I can't say, unequivocally, why Ross did what he did; you can decide for yourself by reading the book. But perhaps not surprisingly, some of his heirs were averse to the idea of selling the plantation, freeing the slaves, and paying their way “back to Africa,” in the vernacular of the times, though most of the slaves had been in America for many generations, and no doubt knew as much about the African continent as a person in Des Moines named O’Reilly knows about Ireland.

After a bitter, decade-long contest of Ross’s and his daughter’s wills by his grandson, Isaac Ross Wade, during which a slave uprising led to the burning of the Prospect Hill mansion, the death of a young girl, and the lynching of a group of slaves, approximately 300 of the slaves did immigrate to Liberia, beginning around 1845, to a parallel universe called Mississippi in Africa. A few of the slaves were not given the option to immigrate, for unknown reasons, and one family was freed outright and allowed to move to a free state in the U.S. What ultimately happened to the ones who were freed outright is still unknown; I hoped my book would spark some revelation about them, but so far, no go.

Because there were many conflicting versions of the story, I set out to find descendants of all the relevant groups in the U.S. and in Liberia. The immigrants from Prospect Hill were the largest group to settle in Liberia, a nation established by the American Colonization Society, which was comprised of abolitionists and slave holders who had different, yet strangely complementary reasons for wanting to export freed slaves. The book Mississippi in Africa was the result of my research; this note was prompted by a reader’s email inquiring about the people I interviewed and got to know during the course of my research.

During that research, which began in the late 1990s, I interviewed Isaac Ross’s descendants in Mississippi, most of whom were proud of his legacy of having freed his slaves (and who, in a curious twist, turned out to be both black and white); I interviewed descendants of the heirs who had contested the will, who had a decidedly different take on the story, and descendants of the slaves who had chosen to remain in Mississippi, enslaved, and, finally, of descendants of the freed slaves who had immigrated to Mississippi in Africa.

In Liberia, which was at the time mired in a bloody civil war, I found that the immigrants had largely assumed the role formerly assigned to their masters, occupying the top tier of Liberian society, and that while some had been benevolent toward those less fortunate than them, others had oppressed and even enslaved members of the indigenous population. That disparity contributed directly to the nation’s two civil wars, from 1989 to 1996 and from 1999 to 2003, illustrating that Dixie isn’t the only place where old times are not forgotten.

The Prospect Hill story became more remarkable the deeper I probed, and along the way I met a remarkable cast of characters who shed light not only on its outcome but on the complex racial dynamics and cultural legacy of Ross’s actions. As readers of the book may recall, among those characters were three young men, the Railey brothers, native Liberians whose ancestors had come from Mississippi, who were, in 2001, when I arrived, trapped in a war zone. The Railey brothers made sure I was safe while I was in Liberia, and we remained in touch for many years. I still occasionally correspond with one of them, Augustus.

I also occasionally get emails from readers who are curious about certain aspects of the story, and I recently heard from one who wondered how the Raileys and a few other people mentioned in the book are faring today. Here was a reader after my own heart, someone who recognizes that no story ever truly ends, that as long as the characters live and breathe, it continues to unfold. I only wish I had more information to impart.

In any event, herewith is what I do know, 10 years later.

In her email, the reader, a woman named Susan Hataway, wrote that she wondered “if the people all survived these past ten years... especially the Railey brothers and Peter Robert Toe and family. Well, actually, I wonder about all of the Raileys including ‘The Old Ma’.”

Among those, Peter Toe Roberts (whose name, I regret to say, I transposed in the book, as Peter Roberts Toe) was the man who was to have guided me to Mississippi in Africa from the nation’s capital, Monrovia, until that plan fell apart. The Old Ma was the Raileys’ grandmother, a delightful, indefatigable woman who had carried on her Mississippi ancestors’ tradition of quilting, at which she was quite accomplished. As far as I know, the Railey brothers themselves – Edward, Kaiser and Augustus -- are all well, but I only know bits and pieces about Peter.

For many years the Railey brothers and I corresponded by phone and by email, as they sought to extract themselves from the poverty and violence of a nation at war with itself. What they really wanted was to go to college, either in the U.S. or at the University of Liberia, in Monrovia. I was never able to find a U.S. university or institution to sponsor them, and it takes money to attend the University of Liberia, which is something that was always in short supply. Theirs was not an easy lot, but the brothers are, if nothing else, persistent.

During our correspondence, I received this thoughtful email from their sister, Princess:

Hi Alan,

Hope you are doing fine as we are. We, my brothers and myself would like to wish you happy belated birthday and pray God's choicest blessings upon you.

Augustus is getting married on the 19th day of July and has chosen you as one of his Patrons. Hope it meets your approval. Have a pleasant Easter as we all retrospect on our risen Lord and Saviour.

Bye for now and stay blessed.

From all of us:

Princess, Kaiser, Augustus and Edward Railey.

Just so you know, a patron, in this context, is just what it sounds like – a benefactor.

In another email, Augustus informed me that their mother and grandmother, the Old Ma, had died within a few months of each other. The Old Ma had suffered a stroke during a meeting to discuss funeral arrangements for another family member. Edward emailed to say that before she died “she asked us as to weather we can still hear from you, and we told her only by e-mail.”

Ouch. OK.

Also since deceased is Rev. Charleston Bailey, a descendant of freed American slaves whom I interviewed, at the Raileys’ suggestion, in Monrovia. Rev. Bailey was a font of information, and I was sorry to hear that he was gone. He was 90, which is impossibly old by Liberian standards.

My other guide while I was in Liberia – he was really more of a “fixer,” in the parlance of journalists, the chief person I relied upon to ensure that I didn’t get into trouble -- was Jefferson Kanmoh, who I identified in the book only as a “student activist” for fear that he would suffer repercussions from the insane and violent government of then-President Charles Taylor. Only after the war ended and Taylor was exiled did I feel comfortable revealing his name.

More than anyone I met there, Jeff, who was imprisoned, nearly starved and was shot during his time as a student activist, serves as a shining beacon for Liberia -- brilliant, fearless, circumspect, noble and morally upright. Once legitimate elections were held in postwar Liberia, he was elected to the national Congress, representing Sinoe County, which encompasses Mississippi in Africa, as well as Louisiana, which was settled by freed slaves from that state. Jefferson and I continue to stay in touch.

Through a mutual acquaintance who introduced us, Jefferson had set me up with the Raileys, and with Peter Toe Roberts, who planned to host me in Mississippi in Africa, before the Taylor government intervened and prevented me from going there. Peter, who endured his own travails, was more or less a doctor in Mississippi in Africa, and, like Jefferson Kanmoh, is an honorable, compassionate and committed man who has saved many lives. He and I remained in touch for several years, but have since lost contact. Sorry, Susan. And sorry, Peter.

I contacted a mutual friend of Peter’s in hopes of finding out how he is getting along, but I haven’t heard back, and my googling produced no results. I did find a younger man named Peter Toe on Facebook who hails from Sinoe County and now lives in Monrovia, but so far I’ve gotten no response to my message asking if he is related to the Peter Roberts I knew. The last word I got about Peter was from an American doctor working for a missionary group who had rented a house from him in Greenville, the capital of Sinoe County, in 2008. At the time, he was doing well.

Another key character, Nathan Ross Sr., the son of a Prospect Hill slave who emigrated to Liberia and fathered him when he was an old man – remarkably, the math adds up -- died in 2004 in Maryland (in the U.S., as opposed to Maryland, Liberia). I have lost touch with his son Nathan Jr., who, at last report, was living in the U.S., and his nephew Benjamin, who I interviewed in Monrovia when he was attempting to emigrate to the U.S.

Among the notable sites I visited in Liberia, two institutions are still in operation: The J.J. Ross High School, a private school in Monrovia established by the Ross immigrants; and the National Museum, which was looted numerous times during the civil war and today houses a collection of only about 100 of its original 6,000-plus artifacts. Fortunately, several historical paintings were protected during the fighting by a man who barricaded himself inside a building across the street to prevent their destruction.

Back in the U.S., Ross descendant Turner Ashby Ross, who I quoted in the book, is also since deceased. But Ann Brown, who helped me piece together the Ross family’s genealogy, is still around, diligently documenting graves throughout Jefferson County. And James Belton, who is descended from Prospect Hill slaves who chose not to emigrate to Liberia, and who filled in some of the most important blanks in the story, is retired now, living in McComb, Miss., busying himself with researching his family history and organizing reunions.

The Prospect Hill house itself, which is the second on the site, having been built in 1854 after the first was burned in the uprising, by Isaac Ross’s grandson (the one who contested the will, and somehow managed to regain the estate), still stands, but it is badly deteriorated. It was recently bought by a New Mexico-based group called the Archaeological Conservancy with the aim of stabilizing it until someone can be found to buy and restore it; the conservancy plans to retain an archaeological easement to ensure that the plantation’s buried artifacts remain available to scholars in hopes that they can shed light on the property’s history.

The conservancy’s regional director, Jessica Crawford, who facilitated the purchase of the house, represents the newest addition to the cast of characters of the Prospect Hill saga, having put in countless hours cleaning out the structure, nailing down rusty tin on the roof, and clearing underbrush from the grounds and the adjacent cemetery, which is the site of a towering monument erected in Isaac Ross’s honor by the Mississippi Colonization Society. Jessica has also located several descendants whom I never came across, and has befriended a peacock left behind by Prospect Hill’s last owner. The peacock is currently the only occupant (unless you count the unidentified growling thing that inhabits the rubble of a collapsed rear room); Jessica named him “Isaac.”

Among the other key figures in the Liberian saga, former Liberian President Charles Taylor remains imprisoned in The Hague following the conclusion, in March 2011, of his three-year trial for alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity in neighboring Sierra Leone during that nation’s civil wars. His judgment is pending.

"Isaac" on the grounds of Prospect Hill; photo by Jessica Crawford

It was a remarkable story that seemed to unravel into thin air. Several versions had been in circulation for generations -- for more than 150 years, in fact. But in each of them the screen went blank just as the plot started getting good.

That's precisely how writers find themselves in the throes of writing a book. Once I heard the story of Mississippi in Africa, I had to know how it ended. How could anyone hear that a group of slaves had emigrated from a Mississippi plantation, decades before the Civil War, to a place in Liberia called Mississippi in Africa, and not want to know what had become of them?

The plot was launched in the 1830s, when an antebellum Mississippi cotton planter and Revolutionary War veteran named Isaac Ross decreed in his will that after his daughter’s death his slaves should be freed and his plantation, called Prospect Hill, should be sold, with the proceeds used to pay the way for the freed slaves to a colony established for the purpose on the coast of West Africa, in what is now the nation of Liberia. A very weird story. I can't say, unequivocally, why Ross did what he did; you can decide for yourself by reading the book. But perhaps not surprisingly, some of his heirs were averse to the idea of selling the plantation, freeing the slaves, and paying their way “back to Africa,” in the vernacular of the times, though most of the slaves had been in America for many generations, and no doubt knew as much about the African continent as a person in Des Moines named O’Reilly knows about Ireland.

After a bitter, decade-long contest of Ross’s and his daughter’s wills by his grandson, Isaac Ross Wade, during which a slave uprising led to the burning of the Prospect Hill mansion, the death of a young girl, and the lynching of a group of slaves, approximately 300 of the slaves did immigrate to Liberia, beginning around 1845, to a parallel universe called Mississippi in Africa. A few of the slaves were not given the option to immigrate, for unknown reasons, and one family was freed outright and allowed to move to a free state in the U.S. What ultimately happened to the ones who were freed outright is still unknown; I hoped my book would spark some revelation about them, but so far, no go.

Because there were many conflicting versions of the story, I set out to find descendants of all the relevant groups in the U.S. and in Liberia. The immigrants from Prospect Hill were the largest group to settle in Liberia, a nation established by the American Colonization Society, which was comprised of abolitionists and slave holders who had different, yet strangely complementary reasons for wanting to export freed slaves. The book Mississippi in Africa was the result of my research; this note was prompted by a reader’s email inquiring about the people I interviewed and got to know during the course of my research.

During that research, which began in the late 1990s, I interviewed Isaac Ross’s descendants in Mississippi, most of whom were proud of his legacy of having freed his slaves (and who, in a curious twist, turned out to be both black and white); I interviewed descendants of the heirs who had contested the will, who had a decidedly different take on the story, and descendants of the slaves who had chosen to remain in Mississippi, enslaved, and, finally, of descendants of the freed slaves who had immigrated to Mississippi in Africa.

In Liberia, which was at the time mired in a bloody civil war, I found that the immigrants had largely assumed the role formerly assigned to their masters, occupying the top tier of Liberian society, and that while some had been benevolent toward those less fortunate than them, others had oppressed and even enslaved members of the indigenous population. That disparity contributed directly to the nation’s two civil wars, from 1989 to 1996 and from 1999 to 2003, illustrating that Dixie isn’t the only place where old times are not forgotten.

The Prospect Hill story became more remarkable the deeper I probed, and along the way I met a remarkable cast of characters who shed light not only on its outcome but on the complex racial dynamics and cultural legacy of Ross’s actions. As readers of the book may recall, among those characters were three young men, the Railey brothers, native Liberians whose ancestors had come from Mississippi, who were, in 2001, when I arrived, trapped in a war zone. The Railey brothers made sure I was safe while I was in Liberia, and we remained in touch for many years. I still occasionally correspond with one of them, Augustus.

I also occasionally get emails from readers who are curious about certain aspects of the story, and I recently heard from one who wondered how the Raileys and a few other people mentioned in the book are faring today. Here was a reader after my own heart, someone who recognizes that no story ever truly ends, that as long as the characters live and breathe, it continues to unfold. I only wish I had more information to impart.

In any event, herewith is what I do know, 10 years later.

In her email, the reader, a woman named Susan Hataway, wrote that she wondered “if the people all survived these past ten years... especially the Railey brothers and Peter Robert Toe and family. Well, actually, I wonder about all of the Raileys including ‘The Old Ma’.”

Among those, Peter Toe Roberts (whose name, I regret to say, I transposed in the book, as Peter Roberts Toe) was the man who was to have guided me to Mississippi in Africa from the nation’s capital, Monrovia, until that plan fell apart. The Old Ma was the Raileys’ grandmother, a delightful, indefatigable woman who had carried on her Mississippi ancestors’ tradition of quilting, at which she was quite accomplished. As far as I know, the Railey brothers themselves – Edward, Kaiser and Augustus -- are all well, but I only know bits and pieces about Peter.

For many years the Railey brothers and I corresponded by phone and by email, as they sought to extract themselves from the poverty and violence of a nation at war with itself. What they really wanted was to go to college, either in the U.S. or at the University of Liberia, in Monrovia. I was never able to find a U.S. university or institution to sponsor them, and it takes money to attend the University of Liberia, which is something that was always in short supply. Theirs was not an easy lot, but the brothers are, if nothing else, persistent.

During our correspondence, I received this thoughtful email from their sister, Princess:

Hi Alan,

Hope you are doing fine as we are. We, my brothers and myself would like to wish you happy belated birthday and pray God's choicest blessings upon you.

Augustus is getting married on the 19th day of July and has chosen you as one of his Patrons. Hope it meets your approval. Have a pleasant Easter as we all retrospect on our risen Lord and Saviour.

Bye for now and stay blessed.

From all of us:

Princess, Kaiser, Augustus and Edward Railey.

Just so you know, a patron, in this context, is just what it sounds like – a benefactor.

In another email, Augustus informed me that their mother and grandmother, the Old Ma, had died within a few months of each other. The Old Ma had suffered a stroke during a meeting to discuss funeral arrangements for another family member. Edward emailed to say that before she died “she asked us as to weather we can still hear from you, and we told her only by e-mail.”

Ouch. OK.

Also since deceased is Rev. Charleston Bailey, a descendant of freed American slaves whom I interviewed, at the Raileys’ suggestion, in Monrovia. Rev. Bailey was a font of information, and I was sorry to hear that he was gone. He was 90, which is impossibly old by Liberian standards.

My other guide while I was in Liberia – he was really more of a “fixer,” in the parlance of journalists, the chief person I relied upon to ensure that I didn’t get into trouble -- was Jefferson Kanmoh, who I identified in the book only as a “student activist” for fear that he would suffer repercussions from the insane and violent government of then-President Charles Taylor. Only after the war ended and Taylor was exiled did I feel comfortable revealing his name.

More than anyone I met there, Jeff, who was imprisoned, nearly starved and was shot during his time as a student activist, serves as a shining beacon for Liberia -- brilliant, fearless, circumspect, noble and morally upright. Once legitimate elections were held in postwar Liberia, he was elected to the national Congress, representing Sinoe County, which encompasses Mississippi in Africa, as well as Louisiana, which was settled by freed slaves from that state. Jefferson and I continue to stay in touch.

Through a mutual acquaintance who introduced us, Jefferson had set me up with the Raileys, and with Peter Toe Roberts, who planned to host me in Mississippi in Africa, before the Taylor government intervened and prevented me from going there. Peter, who endured his own travails, was more or less a doctor in Mississippi in Africa, and, like Jefferson Kanmoh, is an honorable, compassionate and committed man who has saved many lives. He and I remained in touch for several years, but have since lost contact. Sorry, Susan. And sorry, Peter.

I contacted a mutual friend of Peter’s in hopes of finding out how he is getting along, but I haven’t heard back, and my googling produced no results. I did find a younger man named Peter Toe on Facebook who hails from Sinoe County and now lives in Monrovia, but so far I’ve gotten no response to my message asking if he is related to the Peter Roberts I knew. The last word I got about Peter was from an American doctor working for a missionary group who had rented a house from him in Greenville, the capital of Sinoe County, in 2008. At the time, he was doing well.

Another key character, Nathan Ross Sr., the son of a Prospect Hill slave who emigrated to Liberia and fathered him when he was an old man – remarkably, the math adds up -- died in 2004 in Maryland (in the U.S., as opposed to Maryland, Liberia). I have lost touch with his son Nathan Jr., who, at last report, was living in the U.S., and his nephew Benjamin, who I interviewed in Monrovia when he was attempting to emigrate to the U.S.

Among the notable sites I visited in Liberia, two institutions are still in operation: The J.J. Ross High School, a private school in Monrovia established by the Ross immigrants; and the National Museum, which was looted numerous times during the civil war and today houses a collection of only about 100 of its original 6,000-plus artifacts. Fortunately, several historical paintings were protected during the fighting by a man who barricaded himself inside a building across the street to prevent their destruction.

Back in the U.S., Ross descendant Turner Ashby Ross, who I quoted in the book, is also since deceased. But Ann Brown, who helped me piece together the Ross family’s genealogy, is still around, diligently documenting graves throughout Jefferson County. And James Belton, who is descended from Prospect Hill slaves who chose not to emigrate to Liberia, and who filled in some of the most important blanks in the story, is retired now, living in McComb, Miss., busying himself with researching his family history and organizing reunions.

The Prospect Hill house itself, which is the second on the site, having been built in 1854 after the first was burned in the uprising, by Isaac Ross’s grandson (the one who contested the will, and somehow managed to regain the estate), still stands, but it is badly deteriorated. It was recently bought by a New Mexico-based group called the Archaeological Conservancy with the aim of stabilizing it until someone can be found to buy and restore it; the conservancy plans to retain an archaeological easement to ensure that the plantation’s buried artifacts remain available to scholars in hopes that they can shed light on the property’s history.

The conservancy’s regional director, Jessica Crawford, who facilitated the purchase of the house, represents the newest addition to the cast of characters of the Prospect Hill saga, having put in countless hours cleaning out the structure, nailing down rusty tin on the roof, and clearing underbrush from the grounds and the adjacent cemetery, which is the site of a towering monument erected in Isaac Ross’s honor by the Mississippi Colonization Society. Jessica has also located several descendants whom I never came across, and has befriended a peacock left behind by Prospect Hill’s last owner. The peacock is currently the only occupant (unless you count the unidentified growling thing that inhabits the rubble of a collapsed rear room); Jessica named him “Isaac.”

Among the other key figures in the Liberian saga, former Liberian President Charles Taylor remains imprisoned in The Hague following the conclusion, in March 2011, of his three-year trial for alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity in neighboring Sierra Leone during that nation’s civil wars. His judgment is pending.

"Isaac" on the grounds of Prospect Hill; photo by Jessica Crawford

Monday, September 12, 2011

In search of Jan-Michael Vincent

Originally published in Lost magazine.

It started with an old episode of “Gunsmoke,” about a troubled kid in curiously tight pants who brings grief to everyone, including himself, before finding redemption through the decent folks of Dodge City.

TV’s Dodge City was a painted backdrop of a town, fabricated in the sixties to represent all that was popularly viewed as right and wrong about the American frontier. Redemption was a common theme that often took curious forms in Dodge, where the most unassailably upright citizen was U.S. marshal Matt Dillon, who thought nothing of drinking whisky shots, while on duty, in a whorehouse at 10 a.m.

The plot of this particular episode was mildly provocative yet ultimately reassuring, typical of a formula that made “Gunsmoke” the longest running dramatic serial on TV (until it was supplanted by “Law & Order”). Each show revealed something poignant about a character’s life story. The positive forces of the universe usually prevailed in the end. Some of the details in this episode were revealing in other ways, such as that the fledgling actor who played teenaged Travis Colter was the only young man in town who apparently had to be shoe-horned into his pants. That, and the carefully framed shots of his chiseled face, indicate that the director knew what he had to work with, which was a young actor with the makings for a major TV heartthrob.

Guest appearances on “Gunsmoke” were a starting actor’s dream in the sixties and early seventies, much as they are on “Law & Order” today. Among the lucky ones who went on to great things were Harrison Ford, Jodie Foster, Charles Bronson and Kurt Russell. Not all parlayed their appearances into stardom, of course. One frequent guest, Zalman King, became a successful producer of soft porn. Others went into sales. You can find out easily enough through search engines on the Web, if you’re so inclined, which I am.

Like many nosy people today, I need only half an excuse to google anything, and I am particularly interested in stories that illustrate the wildly variable things that can happen to promising people over time. By the time I encountered Travis Colter, I had already developed a habit of wasting potentially productive hours piecing together the random life stories of actors whose careers began as I lay on the floor in front of my family’s black-and-white TV. For this I blame not only myself and Google, but TV Land and Tivo.

When “Gunsmoke” first aired, I was a boy growing up in the quiet suburbs of a sleepy southern town, and one summer day, an actual troubled youth showed up and supposedly tried to kidnap me and my best friend. We were about six years old, sitting barefoot in the grass, watching a steam roller pave our street. I say “supposedly” because I have no way of knowing the man’s intensions. All I know is that he appeared out of nowhere and suggested that we go with him to the creek, and instructed us to go home and get some shoes, then meet him at his car on the corner. Our mothers prevented the follow-through, and another group of women on a nearby street, whose sons had been similarly approached, called the police. After they caught the alleged kidnapper, the police informed our parents that he was 19 years old, the son of a doctor, and had escaped from the local mental institution. That was it. In the years since, I have often wondered what his intentions were, and how his life played out, but there is no way to know. I cannot even google him, because I do not know his name. Finding things out is easier with someone whose life unfurls in full public view. You may never know what it is like to be that person, but you can see the structure of their life in bold relief, and draw your own conclusions about what can happen to people over time.

When the credits rolled on the Travis Colter episode, I learned that the actor who played him was Jan-Michael Vincent, who, I later found, went on to fame in scores of movies and as the star of the eighties show “Airwolf”, which reportedly made him the highest-paid TV actor at the time. One of Vincent’s best known flicks was 1978’s Hooper, starring Burt Reynolds, in which he plays a hunky stuntman who comes up with an idea to pilot a rocket-propelled Trans Am across a gulch. Vincent also appeared on “Lassie”; played a journalist in Nicaragua who falls in love with a beautiful Sandinista (in 1983’s Last Plane Out); was immortalized in a loin cloth in The World’s Greatest Athlete; and hosted the Disney series “The Banana Splits Adventure Hour”. Sadly, my googling also unearthed a darker vein: Vincent’s career eventually ended in a massive train wreck, the result of substance abuse problems. If you can believe what you hear, the marshal of Dodge City wasn’t the only one taking shots at 10 a.m.

It is hard to know how much of what has been said about Vincent is accurate – we’re talking about Internet gossip, for the most part, but there is no question that his career crashed, and that it was related to his drinking. He eventually went on the “Howard Stern Show” no less than four times to talk about it, and his behavior grew increasingly notorious even after his televised confessionals. He was reportedly arrested for public drunk on multiple occasions (one court case, in September 2000, involved his wife of then-three months, whose name was Anna; more on that later). The deal was cinched when Vincent crashed his car and suffered a broken neck and permanently damaged vocal chord. At that point his career was finally disabled. In his last movie, a lamentable gangsta flick called White Boy, released in 2002, Vincent plays a drunk cop whose rheumy eyes look absolutely authentic, and the camera seems intent on exploiting the damage, lingering over the disturbing ruins of his formerly perfect face. After that, Vincent disappeared. A 2004 blog, posted when Vincent was 60, indicated that he was living in seclusion in a remote cabin near Redwood, Mississippi, with a few horses and a female companion who possessed “an outrageous wardrobe.”

In addition to spending hours googling different combinations of anything, I happen to live about 30 miles from Redwood. So while I had only passing interest in Vincent beforehand, I could not ignore the fact that his flaring bottle rocket had spent itself and landed in my own backyard. Redwood, Mississippi is an unassuming encampment of old houses and mobile homes just off Highway 61, a few miles north of Vicksburg, where a line of steep bluffs overlooks the flatlands of the Mississippi Delta. There are waterfalls in the wooded hills and great expanses of brooding swamp below, which give the area a certain presence, but it is not the kind of place that rich, famous, good-looking people dream of ending up. When someone mentions trailers in Redwood, they are not talking about movies. It is, however, a place where a truly outlandish wardrobe might actually set someone apart, and that fact, coupled with the interest that a tragic former movie star naturally engenders, held the promise that Vincent’s strange saga might be attractively within my reach. The more I thought about it, the more it seemed time to log off and hit the road.

I suspected that Vincent had probably abandoned Redwood by now, that his move there had been another in a long series of misadventures, but it’s always nice to have a focus for a leisurely outing, especially if it gives you an excuse to stop everyone you see and ask questions while glancing over their shoulders to see how they decorate their living rooms and what they’re watching on TV. If nothing else, the search held the potential to produce any number of women whose neighbors considered their wardrobes to be in bad taste. It was possible that Vincent really did not want to be bothered, and had moved to Redwood to basically disappear, but if that were the case, it would be evident soon enough and I would leave him alone. All I needed was a little prodding, and it came from my friend Neil, who listened to my idea and said, “Let’s go.”

Neil and I are old friends. We are both former farmers, and for about two days in the eighties I worked as a cowboy on his family’s cattle operation, until I was demoted to carpenter because I was scared of horses. We once made a memorable road trip out West, during which we entertained ourselves with odd characters we encountered against passing backdrops of lonely neon signs and purple crested buttes. The idea of solving the riddle of Jan-Michael Vincent attracted us both for several reasons, not the least of which was the question of how he had ended up in Redwood, Mississippi, of all places. Our interest, I hasten to add, was not of the Brangelina sort, but sprang from a simple fascination with plot. Though Vincent’s one-time celebrity was obviously part of the equation, we were more intrigued by the unfolding tale, which, despite its haplessness, had an epic cast. If we were lucky, perhaps we could view at least one scene from this oversized drama at comparatively close range – something between seeing a movie and actually watching the “based-on” story unfold. As is no doubt painfully obvious, we also had some time on our hands.

It was a balmy day in late November when Neil and I set out for Redwood. Our first stop, just north of Vicksburg, was at an Orbit gas station with a Bud Light sign advertising fresh bait, including worms, minnows, crickets, as well as ice and cold beer. Inside, a friendly woman greeted us from behind the counter. “Can I help you?” she asked. Her smile sagged a little when I asked if she knew where Jan-Michael Vincent lived. “He’s an old actor,” I added. She said sorry, she didn’t know, but that she’d ask. A moment later an older woman with a gray ponytail came out of the kitchen drying her hands. “I’ve heard of him,” she said. “I’ve heard he lives off Redwood Road. I hadn’t met him. I’m just telling you what I’ve heard.” She offered a half-smile, indicating that Vincent’s fame still faintly flickered, though at about the same level of intensity as the burgers sizzling on the griddle behind her. At least it appeared that Vincent was still in the area. We had reason to drive on.

There was another store on the other side of the highway, which was also a barbeque joint. Rural stores typically serve multiple purposes, such as selling gas and groceries, renting movies, and doing your hair and your taxes. A few miles back, on the outskirts of Vicksburg, stood Margaret’s Grocery, which at one time doubled as a bar and church, and presented to passing motorists a candyland façade of red and white striped cinderblock turrets and other fantastically quirky constructs, surmounted by a hand-painted sign proclaiming, “All is Welcome Jew and Gentile.” Inside, an elderly man named Rev. Dennis preached the gospel while his wife sold beer, aspirin and chips to a ragtag band of regulars who sat around playing cards at a table scarred with cigarette burns. In the corner, next to a shelf loaded with paper towels, was a homemade Ark of the Covenant, which Dennis crafted from a wooden box, some castors, a glass doorknob symbolizing the all-seeing eye of God, and some PVC pipe spray-painted gold. At least that’s the way it was the last time I was there, when cats were sleeping in the Ark. We had decided to pass on Margaret’s Grocery this day because it was doubtful that Rev. Dennis had ever heard of Jan-Michael Vincent, and anyway, he always made it so hard to get away. He tended to follow you out to your car, preaching even as you rolled up your window.

In the combo store-barbeque joint we found a group of men in hunting caps drinking coffee at a table. Two others worked the counter. Everyone called out good morning when we came through the door. I approached the counter and asked the older of the two, who turned out to be one of the owners, John Harper, if he perhaps knew anything about a guy named Jan-Michael Vincent. “I sure do,” he said. “He comes in the store all the time. He came in a week or so ago.” This was something of a surprise. We had expected Vincent’s presence to be more of a secret. The younger guy, Shane Davis, added, “He’s got a old girl he lives with. She’s always driving him around. I remember him from movies but he don’t look like that anymore. He’s wore out.” I sensed interest stirring at the table behind me, and one of the coffee drinkers volunteered, “You go up Highway 3 to Ballground, past Ballground Plantation to Bell Bottom Road, past the big ammonia tank. When you get to Bell Bottom Road, it goes straight, and when you come to a curve there’s a house on the right. It’s behind that house.”

“It’s a trailer,” a man in a camo hat said. “But I tell you who you should really talk to: Old Man Henson. He’s 95. He used to be a logger. If you sit up here in the morning with a cup of coffee and ask him a few questions, you’ll be shocked by what he can tell you. How many men you know who logged with oxen? If his knees weren’t bad, he’d work you to death.” Clearly, for him, Old Man Henson and Jan-Michael Vincent existed on the same plane. I liked the idea of talking to Old Man Henson, because who knows, he might have a story to tell, but we had our plans for the day, and anyway Old Man Henson had already gone home.

“The lady he’s with said they live at Eagle Lake now,” Harper said, steering the conversation back to Vincent. “She’s from California someplace, too. Evidently he knew somebody here and he was tired of all that. He don’t get out much now.”

“I live right there by him and I don’t know anything about him,” another of the coffee drinkers reported. “I bet it ain’t one percent of the people in Warren County even knows he lives here.”

“I’ll tell you what you need to be writing a story about: The mayor,” the camo hat said. “He’s corrupt.”

“You can tell at one time she was a looker,” Harper said of Vincent’s companion. “You’d never recognize him. Looks like he’s 90 years old, probably don’t weigh 100 pounds. I was a big fan. I recognized him ’cause I knew he was in the area.” He added, cryptically, “We’re on the barbeque circuit,” then unfurled a barbeque contest poster with pictures of his cooking crew.

Davis, the young guy, added, “They got a convertible Mustang.”

Harper then asked if anyone remembered the movie Vincent was in with Burt Reynolds, but didn’t seem entirely convinced when I said Hooper. At that point it seemed we had pretty much exhausted their Vincent knowledge, so we thanked them and drove on, toward the big ammonia tank at Ballground Plantation. If we didn’t find evidence of Vincent there, we’d try Eagle Lake, about 15 miles to the west.

Contrary to what you might expect, Bell Bottom Road is named not for the pants but for creek bottom land settled by the Bell family. The first thing you see after turning off Highway 3 is an outpost of trailers clustered around a weathered wooden house, in what is essentially a low hollow at the base of the bluffs. On this day, a month or so before Christmas, the landscape was overwrought with lawn decorations, solar sidewalk lights from Wal-Mart, decomissioned appliances, small tractors, both freestanding and trailer-mounted yuletide decorations, and other assorted items that tended to get lost in the dazzle. As with Redwood, one got the impression this was basically an encampment, the only question being: For how long? Some of the trailers were homey and neat, but overall the place expressed tentative, rural disorder.

Most of the residents appeared to be at work, but there were a few operational vehicles parked here and there, so we started at a double-wide whose yard was a fenced corral of small concrete animals. There were the requisite Christmas decorations, an inordinate number of stylized metal suns affixed to the trailer’s front wall, and two identical orange plastic baby swings hanging side by side on the porch. The gate was open.

Approaching a country house unannounced in the middle of a work day is problematic. Everyone has guns, even if they’re just hunting rifles, and owing to the proliferation of crime, strangers are often suspect. Here, the blinds were closed on all the windows, so the place didn’t exactly beckon. Beside the front door was an unexpected fixture that both invited and repelled: An intercom. I pushed the button and a woman’s raspy voice replied, “Can I help you?” A small dog barked in the background. I heard it both through the wall and over the intercom.

“Sorry to bother you,” I said, “but I’m looking for Jan-Michael Vincent. I was wondering if you could help.”

There was a pause, then the disembodied voice croaked back something unintelligible. It was a cheap intercom and the sound quality was poor. I begged the voice’s pardon, asked for a repeat. Speaking more slowly and loudly, which actually emphasized the dissonance, the voice said, “Used to live in that single-wide right in front of my house, but he’s gone. You might check the place across the way, the junky looking one. They might know.”

I glanced back at Neil, who had opted to wait in the truck so we did not seem too threatening, and at the trailers and the rustic house, trying to determine which one looked the junkiest. It was a judgment call.

Back at the truck, we deliberated. There was what could be construed as a junky hodgepodge of used appliances waiting to be recycled beside the house, but in its front yard, directly before it, was the most woebegone mobile home imaginable, rusty and mildewed, with a few broken windows and three washing machines lined up on the sagging porch. It had a shed built over it, perhaps because the roof leaked so badly that it was easier to build another one on top. This, I had just been informed, was lately the home of former movie star Jan-Michael Vincent. It looked grim, so we opted for the house, where a white Chevy truck was parked at an odd angle, as if it had crawled out of the woods. As I approached the house I got an ominous vibe. A chain was wrapped around a porch post, at the end of which was a spiked and glaringly empty dog collar. This menacing country still life evoked all sorts of disturbing sensory images, despite the comparatively welcoming presence of a group of wicker chairs, a porch swing and a barbeque grill nearby. I took one look at the empty dog collar and headed back to the truck. Neil and I agreed that it made sense to leave the driver’s door open so I could beat a hasty retreat if necessary. Then I went back and rang the bell. The blinds, as with the double-wide, were closed. There was no sound from within. After a moment, I gave up.