Thursday, December 29, 2011

"Can I help you find something?"

Writers like to think their work confers upon them a kind of immortality – until they come upon their books in the remainder bin, for a dollar.

Publishing today is more about commerce than literary longevity. It’s like everything else: Most of what’s produced is disposable, trafficked in volume. The days of committed editors developing lifelong relationships with writers honing their craft are gone. Instead, we have publishers whose primary (and in some cases, only) interest is in selling gazillions of mostly formulaic books to ready-made markets. Once a book appears to have peaked in sales, they’re done with it.

My book Mississippi in Africa was published in 2004 and got mostly good reviews, though a couple of reviewers attacked it quite angrily, over comparatively minor things. Writing as a guest reviewer for the New York Times, an aging curmudgeon and “distinguished university professor” named Ira Berlin built his case against the book around a citation it contained – someone else’s citation, mind you, which I cited – that got someone’s name wrong. Here was glaring evidence that I had no idea what I was writing about. Professor Berlin, clearly outraged that a non-academic would have the temerity to write history, proceeded to tell the book’s fascinating story as if it were his own and he’d snatched it from my unworthy hands.

But, I digress.

My point is, after two not-insignificant print runs, in hardback and paperback, my publisher, Penguin Putnam, lost interest in Mississippi in Africa, so they chose not to reprint it and the rights reverted to me. Fearful of the prospects of the book going out of print, I sold the rights to University Press of Mississippi, a small publisher that had done my first book, Ten Point, and has an old-school way of keeping its books in circulation. University Press isn’t exactly at the top of the book marketing game, but, if nothing else, they will keep Mississippi in Africa available into the foreseeable future. Which is not to say readers will be able to find it easily, alas.

I have a habit of looking for my books in whatever bookstore I visit, as I imagine most writers do. I note how many copies are on hand and where the staff chose to display them. It is not unusual for a book to be allotted the premium display space near the front door at the time of its release, only to be assigned to the bargain table a few short years later. It’s a brutal business, publishing.

Sometimes, as I wander a bookstore, I’ll find Mississippi in Africa in the history section; at other times I find it in the southern culture section, the African American section, or the “world” section (whatever that is). Wherever I find it, I typically ask the nearest clerk if they’d like me to sign their copies. Most stores are thrilled for me to do so, because for some reason readers really like it when their books are signed by the author, even if they never met them. I don’t really get this, but I oblige, if only because it attracts customers and the bookstores afterward get me to sign their remaining stock, which they can therefore not return to the publisher, and which they embellish with “Signed by the author” stickers and place in a more prominent display area. Once, for example, after my book Sultana was released, my friend Doug and I went into a bookstore in New York City so he could buy a few copies as gifts. As he was paying for the books he mentioned to the cashier that I was the author. She asked if I’d like to sign their stock. I said of course -- I thought you’d never ask! I then stood by the display, doing the equivalent of a drive-by book signing. No one asked me to prove that I was the author of the book. Afterward Doug and I considered going into another bookstore and announcing that I was some other author, and offering to sign copies of his books. We figured I might be able to pass myself off as William Shakespeare at Books-A-Million, where no one knows anything about, you know, books.

So: Finding my books is a favored pastime, and recently, while Christmas shopping at Lemuria, my hometown bookstore, I noticed that Sultana (“regional interest”) was there, but not Mississippi in Africa, nor, for that matter, Ten Point. Lemuria has always been good to me, hosting author events and giving me an author discount on book purchases, but I’ve noticed my books don’t excite them the same way as, for example, John Grisham’s, for obvious reasons: Lemuria is a store. They sell things. They especially like things they sell a lot of. But not seeing Mississippi in Africa on display during the Christmas season, particularly after its recent re-release, was disappointing, and my disappointment grew as I began actually looking for it in earnest and was unable to find it anywhere.

Eventually Joe, who works there and handles author events, asked if I needed any help. I said, “I don’t see Mississippi in Africa.” Mild panic appeared in Joe’s eyes. He began to scour the shelves – “southern writers,” “African American,” etc., but found nothing. Soon Johnny, who owns Lemuria, walked by and asked what we were looking for. “Mississippi in Africa,” I said, with unconcealed gravity. He then joined in the awkward search, noting, as he did so, that his inventory listed nine copies. I was impressed that he knew this off the top of his head, but it was cold comfort, given that the books could not be discovered by the person who wrote them, nor by the store’s staff. Eventually Johnny found the nine, huddled in the dark corner of a nether shelf – the part where perpendicular shelves adjoin, causing the end of one to be hidden entirely from view. In bookstore terms, this was deepest, darkest Siberia. Johnny pulled them to a more prominent spot. I didn’t even bother to ask about Ten Point, a niche market book that I’m very proud of, but which few stores seem to get.

After Joe and Johnny wandered off, I placed copies of Mississippi in Africa and Sultana in even more prominent positions, to catch potential customers’ eyes, as I always do. Typically I place my books in front of other people’s books that I think are getting too much attention.

I am in the business of selling books, and I admit that the serial dating aspect of the current book-selling market distresses me, and apparently I’m a glutton for punishment, because after I left Lemuria I went to Books-A-Million, a store I loathe, ostensibly because I needed something from the grocery next door and thought I’d pop in and see where they had Mississippi in Africa. As it turned out: Nowhere. I couldn’t find it, and when I asked a clerk, she looked it up on the computer and said, without a hint of regret, “We don’t carry that title.” Thank you for confirming everything I suspected about Books-A-Million! As she delivered this news, a man standing behind me, who had heard the title of the book I was looking for, volunteered, “Don’t believe everything your read in that book” – a comment I uncharacteristically chose to ignore, this being Books-A-Million. I later regretted it, of course. How many chances do you get to call out a hostile reader? Here he was, voluntarily instructing a stranger not to believe what I’d written in my book, not knowing who I was. He was a skinny, country-looking older guy. I would not have expected him to be in the book’s demographic, so I was kind of impressed that he’d even read it, even if he came away dissatisfied. Whatever. I satisfied myself that at least someone in Books-A-Million knew the book existed.

Afterward, I strolled over to the bargain bin to see what I could find. Sometimes you find good stuff there -- I once found Shakespeare in a bargain bin, and I took comfort in that, too.

Friday, December 16, 2011

Two Greenvilles

Who knew? After posting the story about the November 2011 reunion at Prospect Hill Plantation and the two Mississippis, I came across a news item from Sept. 11, 2009, announcing that Greenville, Mississippi (in the U.S.) and Greenville, Liberia (in the area originally known as Mississippi in Africa) are now official sister cities.

Somehow I had missed that development. Serendipitously, a few days later I was informed by Evans Yancy, who is from Greenville, Liberia and now lives in Atlanta, Georgia (in the U.S.), that he had tried, unsuccessfully, to contact me in May 2011 about the sister cities announcement. Evans, who responded to an email from me, didn’t say how he had tried to get in touch, but said that he visited Greenville, Mississippi at that time as a member of the Greenville (Liberia) Development Association. The delegation met with Greenville, Mississippi Mayor Heather McTeer Hudson and the city council.

According to the news item, which ran on the website liberianconsulatega.com, the two Greenvilles entered into a sister city trade agreement in Monrovia, Liberia, with signatories including Honorary Consul General Cynthia Blandford Nash, of Atlanta; Greenville, Mississippi mayoral representative Ed Johnson; Greenville, Liberia Mayor Barbara Ann Moore Keah; and various other dignitaries, mostly from Sinoe County, of which Greenville, Liberia is the capital.

In case you haven’t read previous posts on this site about Prospect Hill and the two Mississippis, Liberia was founded by freed American slaves in the early 19th century and today encompasses regions named for various former homelands of the emigrants, including Georgia, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi and Virginia. In 2003, I published a nonfiction book on the subject titled Mississippi in Africa.

Typically, for sister city agreements, the Greenvilles’ alliance was described as a means “to further friendly diplomatic relations, enhance cultural and historic understanding and cooperation, and to promote international trade between Greenville, Mississippi of the United States of America, and Greenville, Sinoe County of the Republic of Liberia,” according to the news item.

Greenville, Mississippi is one of the more depressed cities in the U.S., located in the poorest region of the poorest state, yet no doubt seems flush compared with war-torn Greenville, Liberia (the nation was in civil war throughout the 1990s and early 2000s).

Coincidentally, Greenville, Mississippi Mayor Hudson is running for the U.S. Congress for District 2, a post currently held by Bennie Thompson. My friend Jefferson Kanmoh, whom I met while researching my book, represents Sinoe County in the Liberian Congress.

Top photo, of Greenville, Liberia, by Scott Harrison; bottom photo, of Greenville, Mississippi, pulled from the internet at cardcow.com.

Sunday, December 11, 2011

Letter from Mississippi

When she mentioned Mississippi, I had to ask which one. Because there are two. There is the one that everyone knows about, in the United States, and there is another, a kind of parallel universe, in the West African nation of Liberia, settled by freed American slaves in the early 19th century.

Evangeline Pelham Wayne is originally from Liberia, where her family owned a plantation-style house on Mississippi Street in Greenville, the capital of the region known as Mississippi in Africa. On a recent autumn day she visited the other Mississippi, in the United States, for an odd reunion of people who had never met, and who were, in a sense, returning to a place most of them had never been.

“When I was growing up in Liberia,” Wayne recalled, “my father always made me spell Mississippi aloud. M-i-s-s-i-s-s-i-p-p-i. If I missed one ‘S’, he’d make me do it again. ‘Try again,’ he’d say. ‘Think about it.’ ‘Think about what?’ I’d say. ‘Why do I have to spell this word?’ His answer: 'One day you'll find out.'”

The recitation of Mississippi’s repetitive crooked letters, humpback letters and “I”s is a childhood ritual in the U.S., but Wayne was baffled by her father’s preoccupation with the word. Years later, as a student at the University of Liberia, she was assigned to write a report about her family history, and by then her father had died, so she convinced her grandmother, Louise Ross Rogers, who was almost 90, to tell her the story. So began a personal journey that eventually led Wayne to the U.S. and, on a recent windy November day, to an abandoned plantation house known as Prospect Hill, in Jefferson County, Mississippi, where she hoped to find clues about her family and her own identity, which is complicated by many factors, on both sides of the Atlantic.

Wayne is a descendant of Africans who were enslaved and taken to the U.S., then allowed to immigrate “back” to Africa in the 1840s, to the freed slave colony in Mississippi in Africa. In 1992, Wayne immigrated “back” to the U.S to escape Liberia’s civil wars, which had begun two years before and would last until 2003, and which were, in many ways, rooted in a long-running conflict between the Americo-Liberians, as the freed slaves and their descendents were known, and indigenous groups, who vastly outnumbered them. Some of the indigenous tribes had been involved in the slave trade when the settlers arrived, and some Americos later enslaved them. Liberia’s history is among the more complicated in Africa, and though Wayne’s family had been there for more than a century and a half, she often felt like an outsider. She spoke no indigenous languages, and neither did any of her family. Now, in the U.S., she said, she is likewise considered a foreigner.

“To be honest, I’m unsure of who, and what, I am, and where I fit in,” she said. "In Liberia or America, I'm considered a foreigner -- someone who does not truly belong."

The event that brought Wayne and her family to Prospect Hill was hosted by the New Mexico-based Archaeological Conservancy, which bought the remote, endangered house in the summer of 2011 in hopes of saving it, along with whatever evidence of its complex history remains buried underground. Jessica Crawford, the conservancy’s regional director, had facilitated the purchase, and afterward was inundated with requests to see the remote, somewhat mysterious property, both from people who had a family connection to it and by others who were simply curious. She decided to hold a private event on the morning of Saturday, Nov. 12, 2011, for those connected to the house, and a public tour in the afternoon, for a suggested donation of $25 per person to a fund to be used for stabilizing the structure. The conservancy’s goal is to stabilize the structure, then resell it to someone who will fully restore and preserve it, while retaining an archaeological easement so that the buried artifacts – around the big house, in the vicinity of the vanished slave quarters and other plantation structures, and in the former fields -- might one day be unearthed and studied.

Gathered on the lawn that morning, before the looming tableau of the dramatically deteriorating house, was an array of people of mixed races, ages and backgrounds who might otherwise have seemed to possess little in common. They included descendants of Prospect Hill’s original slave owners; of plantation slaves who had, during an uprising in 1845, set fire to the previous house on the site; of interracial liaisons between descendents of the former slave holders and slaves in the early 20th century; and of freed plantation slaves who had immigrated, more than 150 years before, to Mississippi in Africa. There was no question about who attracted the most attention: Wayne and her family. The crowd broke into spontaneous applause when the group arrived, more than an hour late, after getting lost of the network of poorly marked local roads.

Being at the center of attention made Wayne a little nervous, partly because the gathering was so freighted, and partly because her own part of the story was riddled with asterisks and asides. She has so far been unable to prove her ancestors’ provenance, though her grandmother mentioned a Mississippi plantation and “Captain Ross,” which Wayne believed to be Prospect Hill and Capt. Isaac Ross, the Revolutionary War veteran who established Prospect Hill and who had enabled the emancipation and emigration of his slaves to Mississippi in Africa in the 1840s. Tracing African American genealogy in the U.S. is a difficult endeavor, because blacks were not included in the census until after the Civil War, but in Liberia it is nearly impossible because most of the nation’s archives were destroyed during the wars. So far, Wayne has been able to document the origins of only one ancestor, who immigrated to Mississippi in Africa from the U.S. state of Georgia. “It seems the connection is there,” she said. “But at this point I can’t be sure.”

Arriving at Prospect Hill brought on a rush of unfamiliar emotions, she said. “Driving in, the closer we got, the odder I felt,” she said. She was exhausted and dazed after driving 18 hours, all night, from suburban Washington, D.C., where she now lives. Her large, expressive eyes were bloodshot, which made her self-conscious because she knew others were observing her closely.

Everyone was looking closely at everyone, but perhaps more so at her and her family, because of who they were, or were believed to be. Wayne’s family represented a sort of triumphal return of the freed Prospect Hill slaves, who had walked away on a cold, rainy winter day in 1845.

Wayne began exploring her family’s possible connection to the place after coming across my nonfiction book, Mississippi in Africa, while researching her family’s history online. She had been researching her family since the early 1990s, but had so far reached nothing but dead ends. It seemed logical that the story would lead from Mississippi in Africa back to its namesake in the U.S., so when she heard about my book she contacted me to ask about Prospect Hill and Capt. Ross.

The subject of the two Mississippis had come up frequently when I visited Liberia in 2001. Roaming the streets of war-torn Monrovia, the nation’s capital, in search of anyone named Ross, I was frequently recognized as an American and asked what state I was from. When I answered “Mississippi,” a common response was, “Me, also!” at which point I would ask, “Mississippi, in Liberia, or Mississippi, in the States?” The answer was almost invariably: “Both.”

Liberians who hailed from the Mississippi region of Liberia were very much aware of the existence of Mississippi in the U.S., and were bewildered that the reverse was not true. Few Americans know anything about Liberia, including where it is. It is often confused with Libya, more than 2,000 miles away. During the civil wars, when Liberians on both sides called for the U.S. to intervene, a smugly ignorant Lou Dobbs warned on his news show that doing so might lead to “another Somalia,” though the two countries are as culturally and geographically distinct as Ireland and Uzbekistan.

Liberia was the first republic in Africa, founded in 1820 (though it did not gain its independence until two decades later) by the American Colonization Society, which was comprised of two groups with seemingly opposed yet overlapping aims: Abolitionists who saw “repatriation,” in the parlance of the times, as a way to make emancipation more politically palatable in the U.S., and slaveholders who were fearful of eventually being outnumbered by free black citizens (some members also saw repatriation as a way to Christianize the indigenous tribes). Liberia is located on the west coast of Africa, where prevailing winds were favorable for ships involved in the North America slave trade. As a result, many of the slaves in the U.S. came from West Africa, which played a role in the decision to repatriate the freed slaves there. Most of the freed slaves had never been to Africa, though, and in some cases were third- or fourth-generation Americans.

The colonial effort, which remains the only one that the U.S. has been directly responsible for, was private, but had the support of the federal government, which occasionally sent warships to quell disputes between the settlers and the indigenous tribes. The settlers, thrust into the wilds of Africa, typically named their communities after familiar places, much like colonial Americans gave their communities names such as New York, New Jersey and New London. In addition to Mississippi in Africa, there are today communities in Liberia known as Louisiana, Georgia and Virginia, and a county named Maryland, all harking to the original emigrants’ home states. The settlers viewed the indigenous groups with a mix of fear, disdain, pity and hostility, much the way British colonials viewed native Americans. Not surprisingly, similar hostilities quickly ensued.

The largest contingent of Liberian emigrants – about 300 – came from Prospect Hill and related family plantations, following a tumultuous decade-long court battle over Isaac Ross’s will, during which a slave uprising led to the burning of the original mansion, the death of a young girl, and the subsequent lynching of a group of slaves believed to have been the perpetrators. Most of the alleged perpetrators were hanged – ostensibly, from a white oak tree on the lawn, part of which momentously fell onto the existing house years ago, and whose dead trunk now lies in the yard, like a menacing stage prop. The house was built in 1854 on the site of the original by Ross’s grandson, who had contested the will and managed to regain the estate after losing it in court (the will had called for Prospect Hill to be sold to pay the way for those of Ross’s slaves who chose to immigrate to Liberia). The slaves who chose not to immigrate worked in the existing house or in the adjacent plantation fields. The house is one of the few remaining landmarks of the entwined histories of the two Mississippis, and in a sense, everyone who attended the reunion was returning to the spot where their parallel stories had diverged. There are many different versions of what happened at Prospect Hill in the 1840s, and afterward in Liberia, and all of them came into play that day; everyone, it seemed, was working from a slightly different script, though with the same key players.

James Belton, whose father was born near the close of the 19th century, is descended from slaves who were involved in the uprising, though the two who directly participated had escaped into the woods, never to be heard from again. Belton’s great grandmother, Mariah Belton, chose not to immigrate to Liberia with her remaining son because she did not want to leave the other two behind. As a result, James Belton grew up in Mississippi, in the U.S., rather than Mississippi in Africa. When he and Wayne met, they came face to face with a person whose life represented what their own might have been like had their ancestors made a different choice in 1845. Neither was quite sure what to say, so they just embraced.

Everyone at the reunion was playing a stand-in role in a drama of profound historical consequence, which conferred new meaning upon their otherwise ordinary lives. James Belton was no longer simply a retired schoolteacher from McComb, Mississippi. He was Mariah Belton’s great grandson, returned to the scene of a major historical crime, which he viewed with a measure of pride and sadness, in that his family had sought to shake free the shackles of slavery, yet had been responsible for the death of the young girl. At one point Belton ventured alone to the Prospect Hill family cemetery, which is dominated by a marble obelisk erected in tribute to Ross by the Mississippi Colonization Society (a state chapter of the American group), and knelt at the grave of the young girl, whose name was Martha.

Later, as Belton spoke to the group about his research and how he had located the descendants of Mariah Belton’s long-lost sons, he was upstaged by a peacock that emerged from the bushes, strutted blithely behind him, then flew, in an awkward, noisy burst of wings, onto what remained of Prospect Hill’s front gallery and disappeared into the darkened parlor. Watching this, in confused silence, were four middle-aged sisters whose grandmother had been the last family member to live in the house, and whose more distant ancestors had fought against the immigration of the Prospect Hill slaves. Behind them was elderly Betty McGehee, descended from the side of the family that had supported the immigration, and so was divided from the sisters’ side. Then there were the descendants of the slaves who did not immigrate, as well as those who did, and finally, a woman and her children who, though they are African American, trace their lineage to Isaac Ross, the man who had set all their stories in motion.

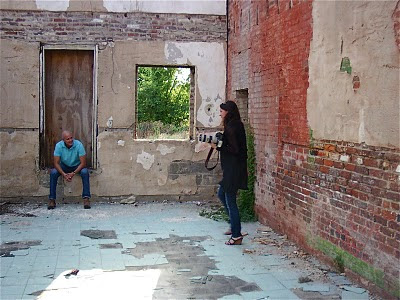

When Crawford first came upon Prospect Hill, on a hot September day in 2010, the structure was overgrown and had been in serious disrepair for decades. Its eccentric last owner had done little maintenance and made almost no repairs, including to the leaky roof, choosing instead to paint interior rooms while exterior woodwork rotted and collapsed onto the ground. Crawford was aware of the plantation’s dramatic history, but that first visit was less like a typical old-house tour than a probe of once beautiful, now sadly deranged mind. The place had been ransacked numerous times and was in such bad shape that she had a hard time even appreciating its grand architecture. Large chunks of plaster had fallen from its 14-foot ceilings; paint was flaking from the elaborate Greek Revival trim; panes were broken in the towering windows, which were partially shrouded by ripped curtains and sagging, gap-toothed shutters. As she picked her way through the dank, shadowy rooms, Crawford observed signs of decay at every turn: Threadbare, moldering rugs, rat-gnawed tables, overturned and emasculated chairs, piles of rain-soaked, mildewed clothes. An empty bourbon bottle protruded from a mass of sodden debris atop a warped grand piano. An array of cooking pots, placed on the floor to catch water from leaks in the roof, had been overflowing for years. Books and papers were scattered everywhere, as if in the aftermath of looting. “It was as if a bomb had gone off inside,” she said.

Considering Prospect Hill’s torturous history, its transformation to a house of minor horrors struck Crawford as sadly appropriate. But for someone devoted to uncovering and preserving clues about the past, the structure’s disfigurement and the seeming inevitability of its loss were unacceptable. She had come to document what remained of the place, yet had not taken a single photo or note as she prepared to leave. “The scenes were just too ugly,” she recalled. “It made me sick.” Then, as she stepped gingerly toward the front door, wanting only to get out, she saw a patch of brilliant color from the corner of her eye. “I looked to the left, and there was this peacock standing in front of the bookcase in the front room,” she said. For the first time, she pulled out her camera and snapped a photo. In it, the peacock stands before a sunlit window, surrounded by fallen books and strewn bags of trash, its head cocked curiously toward her.

The bird had been left behind by the last occupant of the house, and because it was unaccustomed to visitors, quickly vanished from view, though not from Crawford’s memory. On the way home she thought of something her family’s housekeeper had told her when she was a child: As long as there is life in a house, its story isn’t over. As was painfully obvious, there were plenty of living things inside Prospect Hill -- rats, itinerant snakes, a beehive, at least two bats and an entire self-sustaining universe of insects and spiders. But the peacock hinted at a more engaging tale. Crawford chose its image as her take-away.

In subsequent visits, during which she began to clear the encroaching undergrowth and haul away debris, sometimes with the help of volunteers but usually alone, she began to feel an odd connection with the lonely bird, whose showy displays no one typically saw, and which she named Isaac, after Isaac Ross. He enabled Crawford to see past the enervating squalor of the scene, back to the story that had originally brought her there. She also discovered what she came to see as Isaac’s nemesis -- an unseen, unidentified creature that inhabited the debris of a collapsed rear room and growled whenever someone walked nearby. Together, the peacock and the unseen creature provided an allegory of Prospect Hill: On the one hand, the beautiful, unexpected display, and on the other, the hidden, growling thing.

In her effort to save the house, Crawford has inserted herself into a story full of interesting characters, historical and otherwise. After convincing the owner to sell the house, and her boss at the conservancy to buy it – both impressive feats, under the circumstances, Crawford enlisted the help of friends, strangers, descendants, even jail inmates, to return it to a point where it might at least evoke its outsized history. Slowly the house began to reemerge, as Crawford and company prepared it to reprise its role for the reunion. Among those who stumbled upon the house during the period was Tate Taylor, director of the movie The Help, who saw the near-ruins of Prospect Hill from a helicopter. Taylor had recently bought an antebellum house in nearby Church Hill and saw Prospect Hill while flying there from Jackson. He happened to be traveling with a friend, Charles Greenlee, who was descended from Isaac Ross, and the two subsequently returned with a retinue of Hollywood types. Greenlee recalled the strange effect of coming upon the weathered, overgrown house, framed by moss-draped trees, as Isaac, the peacock, greeted them from inside it with a disturbing cry that sent one of the actresses running back toward the car.

Greenlee also attended the reunion event, at which Crawford and representatives of the state’s historic preservation community spoke of the need to preserve the property. Before the conservancy bought the house, the Mississippi Heritage Trust had included Prospect Hill on its 2011 list of most endangered historic structures in the state, and the trust’s director, David Presiozi, spoke during the reunion, as did Jennifer Baughn, chief architectural historian at the state Department of Archives and History. But the formal presentations at the event were mere monologues. The real action took place in conversations between the guests.

Before the event, some of those who planned to attend had expressed concern that there might be tension, and many of the conversations were, in fact, riddled with tiny red flags. One woman asked, more than once, how frequently rape occurred on slave plantations. But for most of those in attendance, the default setting was to be polite. One of the sisters whose grandmother had lived in the house, and whose ancestors had fought against the immigration effort, had earlier wondered aloud how the Liberians would view them. Old times, clearly, are not forgotten, in Dixie or in Liberia, and she was concerned that her family might be perceived as somehow hostile, or be viewed with hostility. Likewise Betty McGehee, who, though she as descended from Isaac Ross and the side of the family that supported freeing the slaves, wondered if her land holdings and heirloom antiques represented “a kind of greed, really -- for me to have these things, and hold onto them?” The question wasn’t an idle exercise; as Wayne observed, McGehee seemed genuinely concerned about how differently her own life had played out than those of others whose paths ran parallel for a while at Prospect Hill. Laura “Butch” Ross, meanwhile, observed that despite the obvious, the story of Prospect Hill was anything but black and white; she was living proof of that, as a black Ross descended from white Rosses.

The stories the people at the reunion shared while roaming the dark rooms of the house, or the cemetery, or while sitting beneath the aged cedar trees, were personal, but had an epic cast, spanning two centuries and two continents. Everyone existed somewhere along the vast network of interconnected circuits, and now the circuits were all lit up for the first time; everyone seemed to want things to go smoothly.

Most, like Crawford, were surprised that the event received little media attention. National Public Radio had initially planned to cover it but later cancelled, saying the story seemed too complicated to explain in radio. Meanwhile, an NPR correspondent was elsewhere in the county, covering a more conventionally black-and-white story, about an unsolved civil rights era murder. All of which meant that the reunion unfolded more or less in private.

Toward the end of the day, as the crowds dispersed, Crawford, Wayne and I departed for dinner on the riverfront in Natchez, a few hours before Wayne and her family would set off on a midnight, marathon return drive to Maryland. As we sat at our table, debriefing each other about the day, Wayne’s thoughts drifted back to the other world -- Liberia. Each time the waiter approached to take our orders, it seemed she was in the middle of describing something tumultuous, and he politely continued on. During the Liberian civil war, her sister was raped and murdered. Wayne herself was accosted by both government forces and rebels, who attempted to kill her husband and two sons, as she wandered the dark streets of Monrovia, in labor, trying to get to the hospital. Her story is full of dramatic asides, both historical and recent, and everyone who had met her that day seemed intent on helping her nail down the necessary details, and to find a kind of closure at Prospect Hill. But like the bigger saga, the day was complicated, and not entirely satisfying. Connections were made, or reestablished, but many, many questions remained. At the center of the cultural mashup was Crawford, who, in a comparatively short time, became a key moderator of the story, as well as the protector of the house, and in her own right, a character in its saga.

Crawford’s goal, initially, was straightforward: To save the archaeological evidence. It soon expanded to encompass the existing house, without which the story would be disembodied. She noted that given the attention that’s recently been focused on Liberia as a result of the awarding of the Nobel Prize to its president as well as a Liberian peace activist and a political activist in Yemen, “It seems like the perfect time to explore the connections that were made there.”

“What struck me,” she added, “is that the place means so much to so many people, for so many – and often very different – reasons.”

Photos by author or courtesy Jessica Crawford

Tuesday, November 8, 2011

Returning to Prospect Hill after 165 years

A very unusual reunion will take place this Saturday at an abandoned plantation in Jefferson County, Mississippi – the haunting, seldom seen Greek Revival house known as Prospect Hill.

Coming together for the first time will be descendants of the plantation’s original slave owners; of a group of slaves who escaped into the woods after setting fire to the first house on the site, in 1845; of slaves who remained on the plantation until their emancipation during the Civil War; and of freed slaves who immigrated from the plantation to the freed-slave colony in Liberia in the 1840s. As if that weren’t enough to get the conversation going, also attending will be descendants of mixed-race liaisons between Prospect Hill’s former slave owners and slaves in the early 20th century.

For $20, you can be a fly on the wall.

Most of the descendents have never seen the place, nor met each other. They’re coming together for an event being staged by the New Mexico-based Archaeological Conservancy, which in August bought Prospect Hill to stabilize the house in hopes of finding a buyer to restore and preserve it. The 10-room structure, which was included in the Mississippi Heritage Trust’s 2011 list of the state’s 10 most endangered historic properties, is one of the few surviving landmarks of a pivotal chapter in American and Liberian history, and it is in danger of being lost.

The story behind Prospect Hill, which was the subject of my 2004 nonfiction book Mississippi in Africa, begins in the 1830s, when Revolutionary War veteran Isaac Ross sought to ensure a better life for his slaves after he and his sympathetic daughter Margaret Reed were gone. Ross and Reed stipulated in their wills that the plantation be sold and the money used to pay the way for those of its slaves who chose to immigrate to a freed-slave colony established for the purpose by a group known as the American Colonization Society. Their destination: A part of the Liberian colony known as Mississippi in Africa.

Ross and Reed no doubt knew their plan would be controversial, but they could not have known how sweeping the impacts would be. Ultimately, they unwittingly set the stage for a tumultuous court battle over the estate, filed by Ross’s grandson, Isaac Ross Wade, and for the divergence, in the 1840s, of the paths of each of the groups that will be represented at Prospect Hill on November 12.

The Rosses and Wades were divided over the repatriation effort, and the slaves themselves were divided over whether to go or stay; likewise, those who sought to immigrate were divided over whether to take matters into their own hands to overcome the obstacles placed in their path to freedom by Wade.

Now, more than 150 years later, their paths will once again converge at Prospect Hill. Among the most notable guests will be 12 Liberians, the adults of whom escaped to the U.S. during their country’s civil war, in the 1990s and early 2000s, which was rooted in the conflict between the freed-slave descendants and Liberia’s indigenous groups; the 12 now live in Maryland.

Some of the descendants will speak at the public event on Saturday afternoon. Also speaking will be Jessica Crawford, with the Archaeological Conservancy; Jennifer Baughn, architectural historian with the state Department of Archives and History; David Preziosi, director of the Mississippi Heritage Trust; and me.

The Archaeological Conservancy hopes the event will draw attention to the intended sale, and meanwhile enable the descendants to compare notes on their related yet conflicting histories for the first time. The Conservancy plans to keep an easement to the Prospect Hill property so that its buried artifacts may one day be studied, and since the purchase Crawford, its southeast regional director, has been laboring to clear the undergrowth that threatened to consume the house, to remove the waterlogged debris from the last owner’s residency, and to undertake emergency repair work on its leaking roof and rotting beams.

The descendants will get a private tour of the property on Saturday morning, with public tours to follow at 1 pm and 2:30 pm. Speakers will discuss the history of the plantation, the house and the adjacent cemetery, site of a monumental obelisk erected in tribute to Ross by the Mississippi Colonization Society in the 1830s.

Prospect Hill and other related family plantations served as the point of embarkation for the largest contingent of emigrants (about 300) to Liberia from the U.S., following Wade’s failed decade-long contest of the estate, during which a slave uprising led to the burning of the first house on the site, the death of a young girl, and the hanging of a group of slaves believed to have been the perpetrators (though at least two escaped into the woods and were never recaptured). A few of the slaves chose not to immigrate to Liberia and remained enslaved, as workers in the existing house (built in 1854) or in the adjacent cotton fields.

The Conservancy is asking for a tax deductible donation of $20 per person to help with the expenses of emergency stabilization work on the house. Anyone interested in attending should call or email to reserve the number of spots needed. Crawford noted that if someone calls and gets voicemail, their call will be returned as soon as possible. The number is 662/326-6465; email is tacsoutheast@cableone.net.

Crawford also stressed that the grounds around the house were recently mowed for the first time in five years, and some of the landscape is rough, so sensible walking shoes are recommended. And because parts of the house are badly deteriorated, a temporary entrance has been constructed for viewing the interior.

Prospect Hill is about 10 minutes east of Lorman, a 45-minute drive from Natchez, about 20 minutes from Port Gibson, and approximately an hour and a half from Jackson. Because the house is comparatively isolated, Crawford suggests that attendees either bring a picnic lunch or have lunch at the Old Country Store in Lorman.

Photo by Jessica Crawford, November 2011

Coming together for the first time will be descendants of the plantation’s original slave owners; of a group of slaves who escaped into the woods after setting fire to the first house on the site, in 1845; of slaves who remained on the plantation until their emancipation during the Civil War; and of freed slaves who immigrated from the plantation to the freed-slave colony in Liberia in the 1840s. As if that weren’t enough to get the conversation going, also attending will be descendants of mixed-race liaisons between Prospect Hill’s former slave owners and slaves in the early 20th century.

For $20, you can be a fly on the wall.

Most of the descendents have never seen the place, nor met each other. They’re coming together for an event being staged by the New Mexico-based Archaeological Conservancy, which in August bought Prospect Hill to stabilize the house in hopes of finding a buyer to restore and preserve it. The 10-room structure, which was included in the Mississippi Heritage Trust’s 2011 list of the state’s 10 most endangered historic properties, is one of the few surviving landmarks of a pivotal chapter in American and Liberian history, and it is in danger of being lost.

The story behind Prospect Hill, which was the subject of my 2004 nonfiction book Mississippi in Africa, begins in the 1830s, when Revolutionary War veteran Isaac Ross sought to ensure a better life for his slaves after he and his sympathetic daughter Margaret Reed were gone. Ross and Reed stipulated in their wills that the plantation be sold and the money used to pay the way for those of its slaves who chose to immigrate to a freed-slave colony established for the purpose by a group known as the American Colonization Society. Their destination: A part of the Liberian colony known as Mississippi in Africa.

Ross and Reed no doubt knew their plan would be controversial, but they could not have known how sweeping the impacts would be. Ultimately, they unwittingly set the stage for a tumultuous court battle over the estate, filed by Ross’s grandson, Isaac Ross Wade, and for the divergence, in the 1840s, of the paths of each of the groups that will be represented at Prospect Hill on November 12.

The Rosses and Wades were divided over the repatriation effort, and the slaves themselves were divided over whether to go or stay; likewise, those who sought to immigrate were divided over whether to take matters into their own hands to overcome the obstacles placed in their path to freedom by Wade.

Now, more than 150 years later, their paths will once again converge at Prospect Hill. Among the most notable guests will be 12 Liberians, the adults of whom escaped to the U.S. during their country’s civil war, in the 1990s and early 2000s, which was rooted in the conflict between the freed-slave descendants and Liberia’s indigenous groups; the 12 now live in Maryland.

Some of the descendants will speak at the public event on Saturday afternoon. Also speaking will be Jessica Crawford, with the Archaeological Conservancy; Jennifer Baughn, architectural historian with the state Department of Archives and History; David Preziosi, director of the Mississippi Heritage Trust; and me.

The Archaeological Conservancy hopes the event will draw attention to the intended sale, and meanwhile enable the descendants to compare notes on their related yet conflicting histories for the first time. The Conservancy plans to keep an easement to the Prospect Hill property so that its buried artifacts may one day be studied, and since the purchase Crawford, its southeast regional director, has been laboring to clear the undergrowth that threatened to consume the house, to remove the waterlogged debris from the last owner’s residency, and to undertake emergency repair work on its leaking roof and rotting beams.

The descendants will get a private tour of the property on Saturday morning, with public tours to follow at 1 pm and 2:30 pm. Speakers will discuss the history of the plantation, the house and the adjacent cemetery, site of a monumental obelisk erected in tribute to Ross by the Mississippi Colonization Society in the 1830s.

Prospect Hill and other related family plantations served as the point of embarkation for the largest contingent of emigrants (about 300) to Liberia from the U.S., following Wade’s failed decade-long contest of the estate, during which a slave uprising led to the burning of the first house on the site, the death of a young girl, and the hanging of a group of slaves believed to have been the perpetrators (though at least two escaped into the woods and were never recaptured). A few of the slaves chose not to immigrate to Liberia and remained enslaved, as workers in the existing house (built in 1854) or in the adjacent cotton fields.

The Conservancy is asking for a tax deductible donation of $20 per person to help with the expenses of emergency stabilization work on the house. Anyone interested in attending should call or email to reserve the number of spots needed. Crawford noted that if someone calls and gets voicemail, their call will be returned as soon as possible. The number is 662/326-6465; email is tacsoutheast@cableone.net.

Crawford also stressed that the grounds around the house were recently mowed for the first time in five years, and some of the landscape is rough, so sensible walking shoes are recommended. And because parts of the house are badly deteriorated, a temporary entrance has been constructed for viewing the interior.

Prospect Hill is about 10 minutes east of Lorman, a 45-minute drive from Natchez, about 20 minutes from Port Gibson, and approximately an hour and a half from Jackson. Because the house is comparatively isolated, Crawford suggests that attendees either bring a picnic lunch or have lunch at the Old Country Store in Lorman.

Photo by Jessica Crawford, November 2011

Wednesday, October 26, 2011

Letting go

I had met this guy the week after Hurricane Katrina. We were on the Mississippi Gulf Coast, surveying the wreckage of historic homes. I didn’t know him well, but now he’d come to visit my home in rural Mississippi, for a party, and we’d driven to the grocery store for some last minute items.

We’d taken his car, and on the way back he drove very, very slowly, which was frustrating because I was in a hurry. My house was already full of people and many more would be arriving later in the day, and he was driving exactly as he’d driven through the debris of Beach Boulevard – about 10 mph, though we were now on a wide-open country road.

Finally, I said, “Do you mind if I drive?” He said OK, so I took the wheel. I don’t remember pulling over to make the switch. Why would I? What mattered was that I was in control. At the next turn – the next-to-last before the drive to my house, I suddenly began to feel disoriented. The world looked unfamiliar. It felt like I’d made a wrong turn, though I’d made the trip thousands of times. I wondered if I was having a seizure or suffering some kind of flashback, or – what? I didn’t know.

The road seemed to unfurl forever, and as I became increasingly unsure of myself, I saw something even more perplexing: We were coming into a town, at a place that should have been open countryside. At that point I became more suspicious than concerned. It occurred to me that I might be dreaming.

As I drove through the unfamiliar town -- which was fairly busy, with lots of people in the streets, coming in and out of gas stations, hardware stores, a small factory of some kind, the Wal-Mart -- I looked for any sign of its name. There were signs everywhere but none that sounded like the name of the town. I mentioned to the Katrina guy that I’d never seen the town before, and didn’t understand how we’d gotten there. It looked like someplace in, maybe, east Texas. He didn’t seem at all concerned. I told him to keep an eye out for a sign that might tell us where we were. Then I glanced at the backseat and saw my friend Paul, who lives in New York City, and who I hadn’t realized was with us. Though it made sense that he’d be coming to the party, the fact that I hadn’t known he was in the car made me more inclined to think I was dreaming, which of course I was.

It’s an odd feeling, to recognize that what seems real isn’t. Naturally, you resist, at first. The first time I remember realizing I was dreaming I was 15 years old, driving with my friends in my mother’s Impala. It was a beautiful summer evening and one of my friends suggested I put the top down, so I did. As we drove, with the wind tousling our hair, it dawned on me that my mother’s car was not a convertible. The only explanation was that I was dreaming. I mentioned this to my friends in the car, who were skeptical and, ultimately, annoyed. “Are you saying I’m not really here?” one of them asked. That was exactly what I was saying, I said. “That’s bullshit,” he said.

Now, as I drove the unfamiliar streets of the seeming east Texas town, I mentioned the convertible dream to Paul and the Katrina guy. I said I know it sounds weird but I think I may be dreaming now. The Katrina guy just shrugged, and continued eyeing the signs, but Paul gave me this distressed look, then vanished. He didn’t want to be a character in someone else’s dream, I guess. Oh, well, I thought. See you back in the waking world!

About that time I noticed an outdoor market up ahead, so I pulled in. I told the Katrina guy I was going to see if I could find a newspaper or something – read the headlines, find a date, just to verify whether this was real. He waited in the car. I approached a stand selling “antique” items – mostly junk, really, which included old newspapers. Here was a stroke of dream-mind brilliance, I thought. There was no way to prove or disprove that this was a dream, based on the newspapers. My mind was trying to trick itself, in plain view. I thought of asking the guy who ran the stand for the date, but it seemed kind of weird to, and anyway he was waiting on customers. So I went back to the car and we drove on. The Katrina guy didn’t even ask if I’d discovered anything. He was, I suppose, the perfect dream-mate.

Down a narrow side street we came upon a river – a very wide river, like the Mississippi. There were many oddly narrow pedestrian promenades angling off from the river, which was flooded. Every river in my dreams is flooded, for some reason, so this was familiar territory. OK, I said, now I know I’m dreaming. I’m sure of it. The street we were on descended into the floodwaters up ahead, remained submerged for a short distance, then returned to dry land. I decided to test my theory and drive into the water. The Katrina guy was alarmed, and put his hand out in front of me, as if to stop me, but I said, Don’t worry, if I’m dreaming we’ll be just fine, and if not, I’ll stop before the water gets too deep. I drove into deep water and kept going. I passed another car, also driving on the river. The Katrina guy got excited when I told him we could do whatever we wanted now -- we didn’t have to worry, because it was a dream. We could fly over buildings if we wanted to – something I’d done numerous times before. I was curious, though, what the dream was going to be about, and was repeatedly thwarted in my efforts to find out. I’ve always assumed that dreams are mechanisms for the brain to explore hypotheticals without repercussion, to help us sort through potential scenarios in our waking lives. For my purposes, however, this resulted in all sorts of dream obstacles. The Katrina guy seemed to be having a good time, even if it was a dream, but he soon vanished, too. I didn’t really notice until I found myself alone, on foot, in an abandoned factory, trying to find my way out.

At this point the dream seemed intent on capturing me, though I knew I was dreaming. Each door I passed through deposited me into an anteroom with another door. It sounds like a potential nightmare, but because I knew I was dreaming I felt a measure of control. Every door opened when I turned the knob. After several passages I realized I was in the middle of a sequence, and I began to count. I was up to seven doors when the last one opened into the sunshine. Once outside, I saw an interesting scene across the street: Some guys working on a water main, talking with a pretty, flirtatious woman. I decided to snap a picture with my cell phone, in part because I still had some minor doubts about whether I was dreaming, and I’d noticed in the past that using my cell phone – including its camera -- was a maddeningly frustrating dream endeavor. Sure enough, though the picture-taking seemed to go OK at first, the screen on my cell phone was unfamiliar and the camera kept snapping pictures before I was ready. Sloppy dream-direction, I thought.

Thus chastened, my dream-mind attempted to exert more control. I walked purposefully back to the truck and got in, drove a short distance, and arrived at my house, which, predictably, was full of guests. Even though I knew I was dreaming, I expected this to be awkward. Not many people like being told they aren’t real, and anything can happen in a dream. A series of frustrating misfires followed. An old girlfriend, waiting for me in bed, asked for a cup of coffee, and when I went into the kitchen I found I couldn’t make any because another woman was using the coffee maker to make some kind of herbal tea, etc. Predictable dream complications. As I waited for the woman to finish, someone asked me to help move some chairs, and a few new guests arrived, and before I knew it, a long time had passed.

Considering that I was at least marginally in control of the setting, and of the unfolding plot, it struck me as odd that I was running into so many problems. If I was dreaming and knew it, why couldn’t I just dispense with the complications? Probably because the complications were the point. I believe dreams can be both psychic and psychiatric exercise, so I am always aware that my control is tenuous. For that matter, even controlling my waking thoughts is sometimes tenuous. Introduce a night-bird that my sleeping ears interprets as the voice of Satan in a dream, which continues to call out after I awake, and all bets are off. In a very profound way, we are all subject to our own dreams.

As I tried to deal with a swelling crowd of imaginary guests, I fiddled with my cell phone, determined that if I could freely move between the waking and the dream world I should be able to find a way to create a record of it – to bridge the gap. This, alas, is how my sleeping mind often occupies itself. It tries to take notes, and even photographs, of an imagined world. It’s hopeless, but I often spend what seems like hours, even days, during a dream, trying to create a waking record of what happened – a note scrawled in a pad on the nightstand, or spray-painted on the wall of a building that I know to be real, to which I might actually return when I’m awake. It never works, but that doesn’t stop me from trying.

In this case, I eventually gave up taking photographs and decided to mentally record what was happening, so that I’d remember the dream once I awakened. I spent the rest of the dream studiously trying to log everything that happened, escaping now and then to a rare quiet place to go over it in my head, to reconstruct everything that had happened from the moment when the Katrina guy was driving to the moment at hand, so I’d be able to review the dream when I was awake, for clues. This is what passes for rest, in my world. This post is the inevitable result. Even in my dreams, I cannot let go.

Dreams are so rich and have such an authentic feeling that scientists have long assumed they must have a crucial psychological purpose, as an article I later read in the New York Times observed. “To Freud, dreaming provided a playground for the unconscious mind; to Jung, it was a stage where the psyche’s archetypes acted out primal themes. Newer theories hold that dreams help the brain to consolidate emotional memories or to work though current problems, like divorce and work frustrations.” OK, the judges will accept that.

The article cited a paper published in the journal Nature Reviews Neuroscience by a psychiatrist and sleep researcher named Dr. J. Allan Hobson, who argued that the main function of rapid-eye-movement sleep, or REM (when most dreaming occurs) is to warm the brain’s circuits for the sights and sounds and emotions of waking. “It helps explain a lot of things, like why people forget so many dreams,” Hobson said. “It’s like jogging; the body doesn’t remember every step, but it knows it has exercised. It has been tuned up. It’s the same idea here: Dreams are tuning the mind for conscious awareness.”

Psychics often claim that dreams are a delivery mechanism for messages from other worlds, and who’s to say they aren’t? I’ve gotten messages from dead loved ones in my dreams, some of which turned out to be true, and which I hadn’t known about before. Psychiatrists have also speculated that dreams are how the brain sorts out its own issues, on its own time. Hobson’s position is that dreaming is a parallel state of consciousness that is continually running but suppressed during waking. If that’s the case, I suppose it’s possible that dreaming is all of those things.

Another neurologist-physiologist cited in the article, Dr. Rodolfo Llinás, countered that dreaming is not a parallel state but is consciousness itself, in the absence of input from the senses. Once people are awake, he argued, their brain essentially revises its dream images to match what it sees, hears and feels -- the dreams are “corrected” by the senses.

In evolutionary terms, according to the Times, REM appears to be a recent development; it is detectable in humans and other warm-blooded mammals and birds. “Studies” suggest that REM makes its appearance very early in life -- in the third trimester for humans, well before a developing child has experience or imagery to fill out a dream. “None of this is to say that dreams are devoid of meaning,” the Times noted. “Anyone who can remember a vivid dream knows that at times the strange nighttime scenes reflect real hopes and anxieties: The young teacher who finds himself naked at the lectern; the new mother in front of an empty crib, frantic in her imagined loss.”

According to the article, “research suggests that only about 20 percent of dreams contain people or places that the dreamer has encountered. Most images appear to be unique to a single dream.” That is most assuredly not the case with me – my dreams have frequent, recurring sets and guest stars, sometimes over the course of years, whom I have never met in my waking life. The scientists claim to know that most dream characters are one-time walk-ons “because some people have the ability to watch their own dreams as observers, without waking up,” the Times reported, at which point I began to feel a now-wakeful sense of disorientation. As an intra-dream observer, I should not be hosting those recurring characters. All of which tells me that if you want answers about dreaming, you’re just as likely to find them in a popular dream-interpretation book. Still, the subject is interesting, particularly when reading about it on the heels of a vivid dream.

The Times continued: “This state of consciousness, called lucid dreaming, is itself something a mystery — and a staple of New Age and ancient mystics. But it is a real phenomenon, one in which Dr. Hobson finds strong support for his argument for dreams as a physiological warm-up before waking.” In dozens of studies, according to the article, researchers have brought people into sleep laboratories and trained them to dream lucidly. “They do this with a variety of techniques, including auto-suggestion as head meets pillow (‘I will be aware when I dream; I will observe’) and teaching telltale signs of dreaming (the light switches don’t work; levitation is possible; it is often impossible to scream).”

Those same sleep researchers contend that lucid dreaming occurs during a mixed state of consciousness, -- “a heavy dose of REM with a sprinkling of waking awareness,” according to the article. Sleepwalking and night terrors, Hobson said, represent mixtures of muscle activation and non-REM sleep. Attacks of narcolepsy reflect an infringement of REM on normal daytime alertness. And what to make of someone, like me, who sleepwalks, has occasional night terrors, and is often aware that he is dreaming? The article didn’t say. Hobson’s point is that those two consciousnesses are separate systems that can operate simultaneously, which begs the question: If a person can be awake enough to recognize he’s dreaming, is the converse true? Could he be awake yet not recognize he’s drifting off into a dream world? Sort of?

Sure enough, the article noted that people who struggle with schizophrenia suffer delusions of unknown origin, but Hobson suggested such flights of imagination may be related to an abnormal activation of a dreaming consciousness. “‘Let the dreamer awake, and you will see psychosis,’ as Jung said,” the Times noted.

“For everyone else, the idea of dreams as a kind of sound check for the brain may bring some comfort, as well,” the article reported. “That ominous dream of people gathered on the lawn for some strange party? Probably meaningless. No reason to scream, even if it were possible.” To which I say: Try telling that to someone who has lost control of their dream, for whom the succession of doors in the anterooms ceases to open.

In my own dream, I eventually left the party that I had virtually thrown but had never quite controlled (even in the dream sense), and decided to go for a run, which is always fun in my dreams because each step spans 10 feet or more and I have boundless energy. As I ran through a darkened city (another familiar landscape in my dreams), I eventually came upon another man, a walker who began to run, too, as I passed. I was singing aloud – this was my dream, so why shouldn’t I? – an original REM song that I was inventing as I went along. I know: REM. Rapid Eye Movement, logically filed beside the band REM in the recesses of my brain. I was enjoying the song because it was at once REM’s and mine. I’d never heard it before. Then, as I ran with the new, unidentified runner beside me, he began to sing along. Eventually I ran out of words – I couldn’t “remember” what I in fact was inventing – but he continued on, singing multiple stanzas. I have no idea who he was – I would have preferred Michael Stipe, but it was his song now, transferred from a hodgepodge of REM sound bites stored in my brain, through my own consciousness, through my dream, to him, an imaginary character who knew more about what was in my brain than I did.

Whatever; finally, I was happy to let go. I let him sing the song, though in a sense it was actually me who was doing the singing, through an imagined character. By then, I guess, the dream had accomplished what it set out to do. My brain had the sensation that it was letting go. When I awoke, I felt at rest, and only wished I’d found a way to write the lyrics down.

We’d taken his car, and on the way back he drove very, very slowly, which was frustrating because I was in a hurry. My house was already full of people and many more would be arriving later in the day, and he was driving exactly as he’d driven through the debris of Beach Boulevard – about 10 mph, though we were now on a wide-open country road.

Finally, I said, “Do you mind if I drive?” He said OK, so I took the wheel. I don’t remember pulling over to make the switch. Why would I? What mattered was that I was in control. At the next turn – the next-to-last before the drive to my house, I suddenly began to feel disoriented. The world looked unfamiliar. It felt like I’d made a wrong turn, though I’d made the trip thousands of times. I wondered if I was having a seizure or suffering some kind of flashback, or – what? I didn’t know.

The road seemed to unfurl forever, and as I became increasingly unsure of myself, I saw something even more perplexing: We were coming into a town, at a place that should have been open countryside. At that point I became more suspicious than concerned. It occurred to me that I might be dreaming.

As I drove through the unfamiliar town -- which was fairly busy, with lots of people in the streets, coming in and out of gas stations, hardware stores, a small factory of some kind, the Wal-Mart -- I looked for any sign of its name. There were signs everywhere but none that sounded like the name of the town. I mentioned to the Katrina guy that I’d never seen the town before, and didn’t understand how we’d gotten there. It looked like someplace in, maybe, east Texas. He didn’t seem at all concerned. I told him to keep an eye out for a sign that might tell us where we were. Then I glanced at the backseat and saw my friend Paul, who lives in New York City, and who I hadn’t realized was with us. Though it made sense that he’d be coming to the party, the fact that I hadn’t known he was in the car made me more inclined to think I was dreaming, which of course I was.

It’s an odd feeling, to recognize that what seems real isn’t. Naturally, you resist, at first. The first time I remember realizing I was dreaming I was 15 years old, driving with my friends in my mother’s Impala. It was a beautiful summer evening and one of my friends suggested I put the top down, so I did. As we drove, with the wind tousling our hair, it dawned on me that my mother’s car was not a convertible. The only explanation was that I was dreaming. I mentioned this to my friends in the car, who were skeptical and, ultimately, annoyed. “Are you saying I’m not really here?” one of them asked. That was exactly what I was saying, I said. “That’s bullshit,” he said.

Now, as I drove the unfamiliar streets of the seeming east Texas town, I mentioned the convertible dream to Paul and the Katrina guy. I said I know it sounds weird but I think I may be dreaming now. The Katrina guy just shrugged, and continued eyeing the signs, but Paul gave me this distressed look, then vanished. He didn’t want to be a character in someone else’s dream, I guess. Oh, well, I thought. See you back in the waking world!

About that time I noticed an outdoor market up ahead, so I pulled in. I told the Katrina guy I was going to see if I could find a newspaper or something – read the headlines, find a date, just to verify whether this was real. He waited in the car. I approached a stand selling “antique” items – mostly junk, really, which included old newspapers. Here was a stroke of dream-mind brilliance, I thought. There was no way to prove or disprove that this was a dream, based on the newspapers. My mind was trying to trick itself, in plain view. I thought of asking the guy who ran the stand for the date, but it seemed kind of weird to, and anyway he was waiting on customers. So I went back to the car and we drove on. The Katrina guy didn’t even ask if I’d discovered anything. He was, I suppose, the perfect dream-mate.

Down a narrow side street we came upon a river – a very wide river, like the Mississippi. There were many oddly narrow pedestrian promenades angling off from the river, which was flooded. Every river in my dreams is flooded, for some reason, so this was familiar territory. OK, I said, now I know I’m dreaming. I’m sure of it. The street we were on descended into the floodwaters up ahead, remained submerged for a short distance, then returned to dry land. I decided to test my theory and drive into the water. The Katrina guy was alarmed, and put his hand out in front of me, as if to stop me, but I said, Don’t worry, if I’m dreaming we’ll be just fine, and if not, I’ll stop before the water gets too deep. I drove into deep water and kept going. I passed another car, also driving on the river. The Katrina guy got excited when I told him we could do whatever we wanted now -- we didn’t have to worry, because it was a dream. We could fly over buildings if we wanted to – something I’d done numerous times before. I was curious, though, what the dream was going to be about, and was repeatedly thwarted in my efforts to find out. I’ve always assumed that dreams are mechanisms for the brain to explore hypotheticals without repercussion, to help us sort through potential scenarios in our waking lives. For my purposes, however, this resulted in all sorts of dream obstacles. The Katrina guy seemed to be having a good time, even if it was a dream, but he soon vanished, too. I didn’t really notice until I found myself alone, on foot, in an abandoned factory, trying to find my way out.

At this point the dream seemed intent on capturing me, though I knew I was dreaming. Each door I passed through deposited me into an anteroom with another door. It sounds like a potential nightmare, but because I knew I was dreaming I felt a measure of control. Every door opened when I turned the knob. After several passages I realized I was in the middle of a sequence, and I began to count. I was up to seven doors when the last one opened into the sunshine. Once outside, I saw an interesting scene across the street: Some guys working on a water main, talking with a pretty, flirtatious woman. I decided to snap a picture with my cell phone, in part because I still had some minor doubts about whether I was dreaming, and I’d noticed in the past that using my cell phone – including its camera -- was a maddeningly frustrating dream endeavor. Sure enough, though the picture-taking seemed to go OK at first, the screen on my cell phone was unfamiliar and the camera kept snapping pictures before I was ready. Sloppy dream-direction, I thought.

Thus chastened, my dream-mind attempted to exert more control. I walked purposefully back to the truck and got in, drove a short distance, and arrived at my house, which, predictably, was full of guests. Even though I knew I was dreaming, I expected this to be awkward. Not many people like being told they aren’t real, and anything can happen in a dream. A series of frustrating misfires followed. An old girlfriend, waiting for me in bed, asked for a cup of coffee, and when I went into the kitchen I found I couldn’t make any because another woman was using the coffee maker to make some kind of herbal tea, etc. Predictable dream complications. As I waited for the woman to finish, someone asked me to help move some chairs, and a few new guests arrived, and before I knew it, a long time had passed.

Considering that I was at least marginally in control of the setting, and of the unfolding plot, it struck me as odd that I was running into so many problems. If I was dreaming and knew it, why couldn’t I just dispense with the complications? Probably because the complications were the point. I believe dreams can be both psychic and psychiatric exercise, so I am always aware that my control is tenuous. For that matter, even controlling my waking thoughts is sometimes tenuous. Introduce a night-bird that my sleeping ears interprets as the voice of Satan in a dream, which continues to call out after I awake, and all bets are off. In a very profound way, we are all subject to our own dreams.

As I tried to deal with a swelling crowd of imaginary guests, I fiddled with my cell phone, determined that if I could freely move between the waking and the dream world I should be able to find a way to create a record of it – to bridge the gap. This, alas, is how my sleeping mind often occupies itself. It tries to take notes, and even photographs, of an imagined world. It’s hopeless, but I often spend what seems like hours, even days, during a dream, trying to create a waking record of what happened – a note scrawled in a pad on the nightstand, or spray-painted on the wall of a building that I know to be real, to which I might actually return when I’m awake. It never works, but that doesn’t stop me from trying.

In this case, I eventually gave up taking photographs and decided to mentally record what was happening, so that I’d remember the dream once I awakened. I spent the rest of the dream studiously trying to log everything that happened, escaping now and then to a rare quiet place to go over it in my head, to reconstruct everything that had happened from the moment when the Katrina guy was driving to the moment at hand, so I’d be able to review the dream when I was awake, for clues. This is what passes for rest, in my world. This post is the inevitable result. Even in my dreams, I cannot let go.

Dreams are so rich and have such an authentic feeling that scientists have long assumed they must have a crucial psychological purpose, as an article I later read in the New York Times observed. “To Freud, dreaming provided a playground for the unconscious mind; to Jung, it was a stage where the psyche’s archetypes acted out primal themes. Newer theories hold that dreams help the brain to consolidate emotional memories or to work though current problems, like divorce and work frustrations.” OK, the judges will accept that.

The article cited a paper published in the journal Nature Reviews Neuroscience by a psychiatrist and sleep researcher named Dr. J. Allan Hobson, who argued that the main function of rapid-eye-movement sleep, or REM (when most dreaming occurs) is to warm the brain’s circuits for the sights and sounds and emotions of waking. “It helps explain a lot of things, like why people forget so many dreams,” Hobson said. “It’s like jogging; the body doesn’t remember every step, but it knows it has exercised. It has been tuned up. It’s the same idea here: Dreams are tuning the mind for conscious awareness.”

Psychics often claim that dreams are a delivery mechanism for messages from other worlds, and who’s to say they aren’t? I’ve gotten messages from dead loved ones in my dreams, some of which turned out to be true, and which I hadn’t known about before. Psychiatrists have also speculated that dreams are how the brain sorts out its own issues, on its own time. Hobson’s position is that dreaming is a parallel state of consciousness that is continually running but suppressed during waking. If that’s the case, I suppose it’s possible that dreaming is all of those things.

Another neurologist-physiologist cited in the article, Dr. Rodolfo Llinás, countered that dreaming is not a parallel state but is consciousness itself, in the absence of input from the senses. Once people are awake, he argued, their brain essentially revises its dream images to match what it sees, hears and feels -- the dreams are “corrected” by the senses.

In evolutionary terms, according to the Times, REM appears to be a recent development; it is detectable in humans and other warm-blooded mammals and birds. “Studies” suggest that REM makes its appearance very early in life -- in the third trimester for humans, well before a developing child has experience or imagery to fill out a dream. “None of this is to say that dreams are devoid of meaning,” the Times noted. “Anyone who can remember a vivid dream knows that at times the strange nighttime scenes reflect real hopes and anxieties: The young teacher who finds himself naked at the lectern; the new mother in front of an empty crib, frantic in her imagined loss.”

According to the article, “research suggests that only about 20 percent of dreams contain people or places that the dreamer has encountered. Most images appear to be unique to a single dream.” That is most assuredly not the case with me – my dreams have frequent, recurring sets and guest stars, sometimes over the course of years, whom I have never met in my waking life. The scientists claim to know that most dream characters are one-time walk-ons “because some people have the ability to watch their own dreams as observers, without waking up,” the Times reported, at which point I began to feel a now-wakeful sense of disorientation. As an intra-dream observer, I should not be hosting those recurring characters. All of which tells me that if you want answers about dreaming, you’re just as likely to find them in a popular dream-interpretation book. Still, the subject is interesting, particularly when reading about it on the heels of a vivid dream.

The Times continued: “This state of consciousness, called lucid dreaming, is itself something a mystery — and a staple of New Age and ancient mystics. But it is a real phenomenon, one in which Dr. Hobson finds strong support for his argument for dreams as a physiological warm-up before waking.” In dozens of studies, according to the article, researchers have brought people into sleep laboratories and trained them to dream lucidly. “They do this with a variety of techniques, including auto-suggestion as head meets pillow (‘I will be aware when I dream; I will observe’) and teaching telltale signs of dreaming (the light switches don’t work; levitation is possible; it is often impossible to scream).”

Those same sleep researchers contend that lucid dreaming occurs during a mixed state of consciousness, -- “a heavy dose of REM with a sprinkling of waking awareness,” according to the article. Sleepwalking and night terrors, Hobson said, represent mixtures of muscle activation and non-REM sleep. Attacks of narcolepsy reflect an infringement of REM on normal daytime alertness. And what to make of someone, like me, who sleepwalks, has occasional night terrors, and is often aware that he is dreaming? The article didn’t say. Hobson’s point is that those two consciousnesses are separate systems that can operate simultaneously, which begs the question: If a person can be awake enough to recognize he’s dreaming, is the converse true? Could he be awake yet not recognize he’s drifting off into a dream world? Sort of?

Sure enough, the article noted that people who struggle with schizophrenia suffer delusions of unknown origin, but Hobson suggested such flights of imagination may be related to an abnormal activation of a dreaming consciousness. “‘Let the dreamer awake, and you will see psychosis,’ as Jung said,” the Times noted.